Simple Geometry, Deep Math

Introduction

It is a remarkable fact that consideration of very elementary concepts in geometry often leads quickly into deep and unexpected mathematical terrain. In high school and even college, such complexities are usually treated cursorily or omitted altogether, in order to avoid bogging down coverage of the essentials. In this article, we delve, at least a bit, into some of the fascinating areas inextricably linked to even the simplest geometric figures.

The Number Line and Infinity

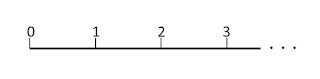

Consider the (non-negative) number line, familiar from grade school and used in high school analytic geometry:

Certainly, it includes the whole numbers, also known as "integers," as shown above. When you think about it, that already puts us in deep territory, because there are an infinite number of integers.

Furthermore, we know that there are numbers on this line, fractions, between the integers. In fact, if n is any integer, the sequence of fractions \(n+\frac 1 2,~n+\frac 1 3,~n+\frac 1 4,~n+\frac 1 5,~...\) shows that there are an infinite number of fractions between any two integers and that there are fractions arbitrarily close to any integer. These facts rather puzzled the ancient Greeks (see, for example, Zeno's Dichotomy Paradox.)

In general, a fraction is any ratio \(\frac n m\), where n and m are integers. Fractions are thus more formally called "rational" numbers. (The integers are included as rational numbers, since m can be 1.) It is easy to show that between any two rational numbers, no matter how close, there are an infinite number of other rational numbers. Pretty amazing to think about!

The Square and Irrationals

More weirdness arises as soon as we consider a very simple geometric figure, the square. Suppose a square's sides each have length 1. What is the length of the square's diagonal, that is, a line connecting its opposite corners? A simple computation using that old friend from high school, the Pythagorean Theorem, shows that the diagonal has length \(\sqrt 2~\) (i.e., the "square root of 2," the number which when multiplied by itself gives 2.)

\(\sqrt 2~\) is clearly somewhere between 1 and 2 on the number line. However, one can prove that \(\sqrt 2~\) is not a rational number! (Actually, there are many easy proofs of this fact; see this Physics Forums tutorial.) So what kind of bizarre number is it? The ancients were aware of this mystery, as well, and it really freaked them out! (The legend of Hippasus illustrates their reaction.)

There are actually many numbers that are not rational. Not surprisingly, they are known as "irrational" numbers. In fact, it turns out that between any two numbers (rational or irrational) on the number line, no matter how close, there are an infinite number of irrational numbers! Yes, there's room for those, too!

Irrationals are perfectly bona fide numbers; however, we can't write out their values in any simple way. Instead, we must specify them as the limit of an infinite sequence of rational numbers, usually as the "value" of an infinite rational sum (or "series.") For example, according to Wikipedia's article on the square root of 2, one such sum is:

$$\sqrt 2\,={\frac {1}{2}}+{\frac {3}{8}}+{\frac {15}{64}}+{\frac {35}{256}}+{\frac {315}{4096}}+{\frac {693}{16384}}+\cdots$$

However, we normally express an irrational number as a particular kind of infinite rational sum, i.e., the familiar decimal expansion. For example,

$$\begin{align} \sqrt 2 & = 1+\frac 4 {10}+\frac 1 {100}+\frac 4 {1000}+\frac 2 {10000}+\frac 1 {100000}+\frac 3 {1000000}+\frac 5 {10000000}+\cdots \\ & = 1.4142135... \end{align}$$(Rational numbers can also be written this way. For instance, \(\frac {29} {11} = 2.63636363...\) However, rational decimals always end in a repeating pattern of digits, which is never true of irrationals.)

Of course, although such representations are infinite, we can obtain the value to any desired precision by simply carrying out the expansion far enough. To put it another way, we approximate an irrational number with a rational number that is close to it. That rational can be as close to the irrational as we like, assuming we are willing to expend the effort to calculate it, but (by definition!) we can never get all the way to the irrational, itself.

Nowadays, because numbers like \(\sqrt 2\) are introduced early in secondary school and we're used to computing their (approximate) values easily with digital devices, we may not stop to think how strange and intriguing irrational numbers truly are.

The Circle and Transcendentals

Returning to geometry, let's look at the simplest figure of all: a circle. If its diameter has length 1, what is its circumference? Of course, it's that famous number we call \(\pi\) (pi), whose decimal expansion begins \(3.14159...\) Perhaps it comes as no surprise that \(\pi\) is an irrational number. But remarkably, this fact was not proved until the 18th century!

Starting with the irrational \(\sqrt 2\), you can "get back" to a rational number (i.e., 2) by simply multiplying it by itself. Many other irrationals compute to rationals by successive self-multiplication, multiplication by various rationals, and addition of such terms (forming what is known as a "polynomial with rational coefficients.") If a number can be "converted" to a rational using simple algebraic operations in this way, it is called an "algebraic" number.

Obviously, all rational numbers are algebraic. Until the 19th century, it was an open question whether or not all irrational numbers are algebraic, as well. Eventually, it was proved that non-algebraic numbers do exist. Such numbers are called "transcendental," and they are extremely hard to find. In 1882, it was proved that \(\pi\) is transcendental! As it happens, that other famous number known as "e" was found to be transcendental slightly earlier, in 1873.

To this day, it is not known whether such simple combinations as \(\pi+e\) or \(\pi\cdot{e}\) are transcendental -- or even whether they are irrational! Yet, incredibly, it was established in the 1870's that there are actually more transcendental numbers than algebraic numbers on the number line!

The Ellipse and -- a Surprise!

Although \(\pi\) is a strange number, at least the geometric formulas in which it appears are often quite simple. For example, consider a circle with radius r:

You may recall that the circle's area is \(\pi{r^2}\) and its circumference is \(2\pi{r}\).

What about an ellipse? (Click here for definition.) Below we picture an ellipse with semi-axes \(r_1\) and \(r_2\) (sort of the equivalent of radii):

It is well-known that the ellipse has area \(\pi{r_1}{r_2}\), a formula analogous to the circle's. So one might suppose that the ellipse's circumference would be (averaging the "radii"): \(2\pi\frac {r_1+r_2} 2 = \pi(r_1+r_2)\) Unfortunately, it turns out this is not the case.

The astonishing truth is that there is no formula, at all, for the circumference of an ellipse! At least, not an ordinary ("closed form") one. Nevertheless, various expressions for the value have been devised that involve an infinite series. Here is one example: $$\pi (r_1+r_2)\left[1+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }\left({\frac {(2n-3)!!}{2^{n}n!}}\right)^{2}\left(\frac {r_1-r_2} {r_1+r_2}\right)^{2n}\right]$$ So much for simple geometry!

Using the language of calculus, a slightly more elegant way of writing the circumference of an ellipse is: $$4{r_1}\int _{0}^{\pi /2}{\sqrt {1-\left(1-{\frac {{r_2}^2} {{r_1}^2}}\right)\sin ^{2}\theta }}\,\,\ d\theta$$

However, this integral cannot be directly evaluated. In fact, the study of such "elliptic integrals," which began in the 18th century, eventually led to whole new areas of mathematics, such as "elliptic functions" and "elliptic curves." These are active and fruitful subjects of research even today, although they no longer have much to do with actual ellipses. But at this point I'm getting way out of my depth...!