Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around the concept of partial derivatives in the context of quantum mechanics, specifically addressing the apparent contradictions that arise when calculating the partial derivative of an observable Q with respect to time t, given that other variables may also depend on t. Participants explore the implications of these derivatives in both classical calculus and quantum mechanics.

Discussion Character

- Debate/contested

- Technical explanation

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

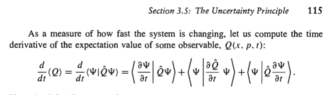

- Some participants assert that the partial derivative ∂Q/∂t should yield a single consistent result, while others present different expressions for Q leading to different derivatives.

- It is noted that when calculating ∂Q/∂t, one must consider how x depends on t, as x is not held constant.

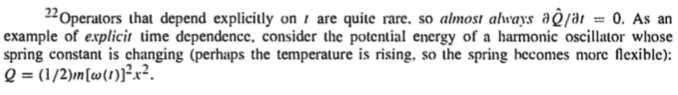

- Some participants clarify that ∂Q/∂t refers specifically to the partial derivative and not the total derivative, emphasizing that only the explicit dependence of Q on t should be considered.

- One participant introduces the concept of operators in quantum mechanics, stating that time t is not an observable and thus not an operator, while position x is represented by a self-adjoint operator.

- There is a discussion about the implications of the Schrödinger equation and how it relates to the time evolution of quantum states, with references to expectation values and the definition of velocity in quantum mechanics.

- Some participants express uncertainty about whether the original contradiction regarding the value of

is resolved by considering different forms of x.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants do not reach a consensus, as there are multiple competing views on how to interpret the partial derivatives and their implications in quantum mechanics. The discussion remains unresolved regarding the correct approach to calculating these derivatives.

Contextual Notes

Limitations include the dependence on how variables are defined and the potential confusion between partial and total derivatives. The discussion also highlights the distinction between classical calculus and quantum mechanics, particularly regarding observables and operators.