TeethWhitener said:

The point of calibration is to try to mitigate differences across instruments and instrument settings. Ideally, if you know the instrument response exactly, the absolute Raman cross section of a peak (the part most closely corresponding to ##\langle f| \alpha | i \rangle##) is the integrated area of the peak. But this still is dependent on wavelength, sample geometry, etc., etc. Here’s what looks like a decent reference on Raman calibration at first glance:

https://www.thevespiary.org/library...tometric.Standards.for.Raman.Spectroscopy.pdf

You can see that the community has pretty much come to a consensus about the value of a handful of cross sections (the article mentions the benzene 992 resonance in particular) and calibrate all instruments according to those.

The reason this question is so tough is because the scattering cross sections and the instrument responses

both change with wavelength. So let’s say for example you have an excitation wavelength of 532 nm. The resonance at 800 cm

-1 is at a wavelength of around 560 nm, while the resonance at 2800 cm

-1 is at around 625 nm. You need a standard at each of those wavelengths to know the instrument response, but you need to know the instrument response to know how the standard should behave at those wavelengths. It’s a bootstrapping problem.

I'm aware of this bootstrapping problem. But this can be wholly addressed by luminescent source calibration, right? Or still not complete and why? I read in your reference:

"

The article describes three steps toward achievement of

a corrected Raman spectrum which accurately represents

the scattering intensity of a given sample as a function of

Raman shift:

1. Reproducibility of observed scattering intensity.

2. Correction for variation of instrument response across

a Raman spectrum.

3. Determination of absolute scattering intensity and absolute

Raman cross-sections.

As discussed below, the first two objectives may be

achieved by straightforward calibration, while the third is

much more involved. Fortunately, the great majority of

Raman applications do not require assessment of absolute

intensity, with the accompanying experimental difficulties.

Reproducible Raman intensities may be achieved with sensible

design of sampling optics and reasonable experimental

care. Although response function correction is not yet routine,

it is readily applied and quite useful. The result of

these two calibration steps is a Raman spectrum which

accurately reflects relative Raman scattering intensities and

is useful for library searching, quantitative analysis, and

comparison of spectra between laboratories. Current applications

of Raman spectroscopy can be broadened significantly

without calibrating absolute intensity, and absolute

measurements of cross-sections are generally left to the

specialist."

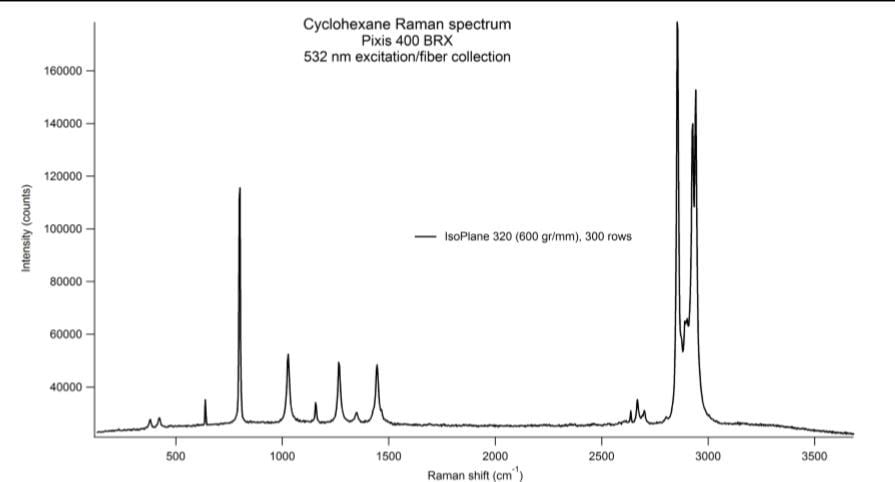

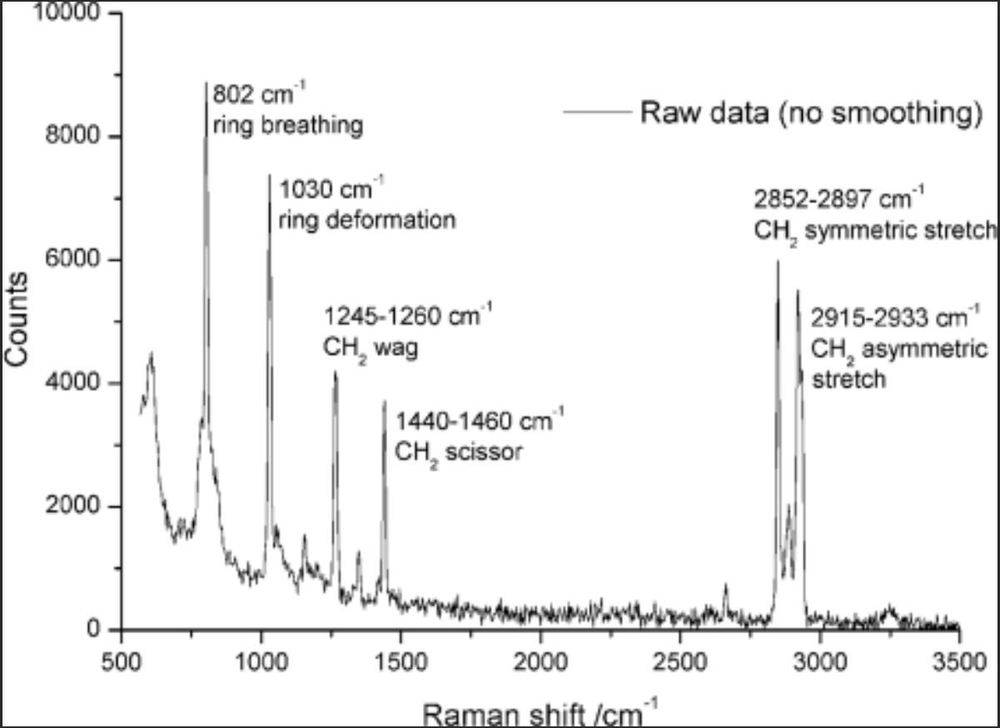

In above, the 802 cm-1 peak is higher. But elsewhere (for example from https://www.princetoninstruments.com/userfiles/files/assetLibrary/Technical%20posters/Poster-Aberration-Free-Raman-Spectroscopy-with-the-IsoPlane.pdf ) the 2853 cm-1 peak is higher.

In above, the 802 cm-1 peak is higher. But elsewhere (for example from https://www.princetoninstruments.com/userfiles/files/assetLibrary/Technical%20posters/Poster-Aberration-Free-Raman-Spectroscopy-with-the-IsoPlane.pdf ) the 2853 cm-1 peak is higher.