etotheipi

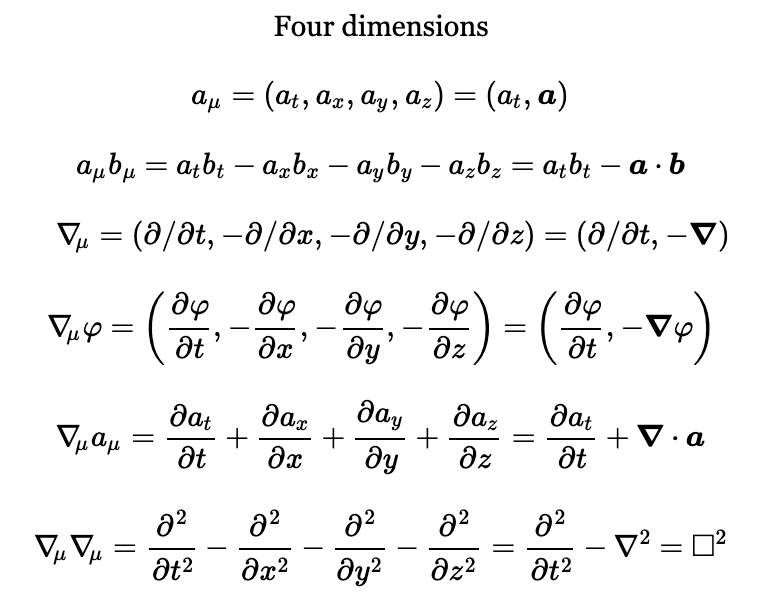

I found some parts of Vol II, Chapter 25 basically unreadable, because I can't figure out his notation. AFAICT he's using a (+,-,-,-) metric, but these equations don't really make any sense:

The first one is fine, and so is the second so long as we switch out ##a_{\mu} b_{\mu}## for ##a_{\mu} b^{\mu}##. But I'm pretty certain the second one should be$$\nabla_{\mu} = (\partial_t, \partial_x, \partial_y, \partial_z) = (\partial_t, \nabla)$$whilst the fifth should be$$\nabla_{\mu} a^{\mu} = \partial_t a^t + \partial_x a^x + \partial_y a^y + \partial_z a^z = \partial_t a_t - \partial_x a_x - \partial_y a_y - \partial_z a_z = \partial_t a_t - \nabla \cdot \mathbf{a}$$and finally the sixth is okay, but again only so long as we switch out ##\nabla_{\mu} \nabla_{\mu}## for ##\nabla_{\mu} \nabla^{\mu}##.

One might argue that he's put everything downstairs to avoid confusion (!), but given that index placement is of such importance when we have a metric that is not the identity, I wonder if there's a subtlety to his notation that I missed? Thank you.

The first one is fine, and so is the second so long as we switch out ##a_{\mu} b_{\mu}## for ##a_{\mu} b^{\mu}##. But I'm pretty certain the second one should be$$\nabla_{\mu} = (\partial_t, \partial_x, \partial_y, \partial_z) = (\partial_t, \nabla)$$whilst the fifth should be$$\nabla_{\mu} a^{\mu} = \partial_t a^t + \partial_x a^x + \partial_y a^y + \partial_z a^z = \partial_t a_t - \partial_x a_x - \partial_y a_y - \partial_z a_z = \partial_t a_t - \nabla \cdot \mathbf{a}$$and finally the sixth is okay, but again only so long as we switch out ##\nabla_{\mu} \nabla_{\mu}## for ##\nabla_{\mu} \nabla^{\mu}##.

One might argue that he's put everything downstairs to avoid confusion (!), but given that index placement is of such importance when we have a metric that is not the identity, I wonder if there's a subtlety to his notation that I missed? Thank you.