RohanJ

- 18

- 2

- TL;DR

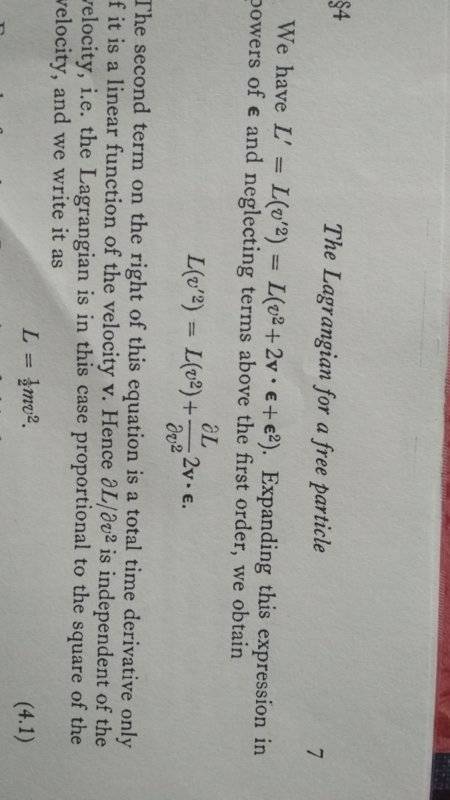

- Discussion leading to Lagrangian for a free particle being (mv^2)/2

In Landau mechanics it's been given that multiple Lagrangians can be defined for a system which differ by a total derivative of a function.

This statement is further used for the following discussion.

I understand that the term for L has been expanded as a Taylor series but I can't understand the statement given just after that claims that partial derivative of L w.r.t v^2 is independent of the velocity.Can anyone lead me through it mathematically?

This statement is further used for the following discussion.

I understand that the term for L has been expanded as a Taylor series but I can't understand the statement given just after that claims that partial derivative of L w.r.t v^2 is independent of the velocity.Can anyone lead me through it mathematically?