Reverend Shabazz

- 19

- 1

Hello all,

I'm reading through Jackson's Classical Electrodynamics book and am working through the derivation of the Legendre polynomials. He uses this ##\alpha## term that seems to complicate the derivation more and is throwing me for a bit of a loop. Jackson assumes the solution is of the form:

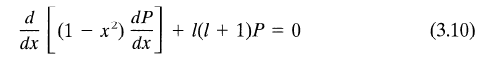

Inserting this into the differential equation we need to solve,

,

,

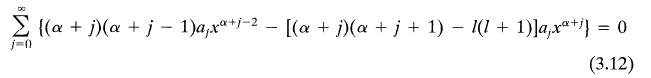

we obtain:

He then says:

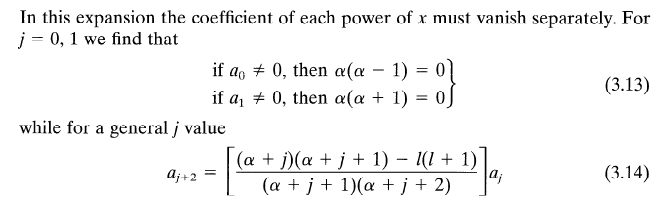

,

,

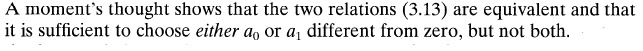

which I agree with. The issue I'm having is with the next statement:

First, in saying the two relations are equivalent, I assume he means that if ##a_0 \neq 0## then we have ##P(x)_{a_0 \neq 0} = P_{\alpha=0}(x) + P_{\alpha=1}(x)##

##= a_0 +a_1*x^1+a_2*x^2 +...## ##+## ##a_0'*x^1+a_1'*x^2+a_2'*x^3 +...##

whereas if ##a_1 \neq 0## then we have ##P(x)_{a_1 \neq 0} = P_{\alpha=0}(x) + P_{\alpha=-1}(x)##

##= a_0 +a_1*x^1+a_2*x^2 +...## ##+## ##a_0''*x^{-1}+a_1''+a_2''*x^1+...##

and, setting ##a''##=0 to avoid the potential blowing up at x=0, ##P(x)_{a_0 \neq 0}## is basically the same as ##P(x)_{a_1 \neq 0}##, since each can be expressed as an infinite series in the form of ##c_0+c_1*x^1+c_2*x^2+...##. Therefore, we can choose either ##a_0 \neq 0## or ##a_1 \neq 0##.

But then he says we can't have both ##a_0 \neq 0## and ##a_1 \neq 0##, which I don't quite follow. If they were both 0, we'd need ##\alpha \equiv 0 ## (to satisfy his eq 3.13) and the solution would be of the form ##a_0+a_1*x^1+a_2*x^2+...##. What's wrong with that at this point in the derivation?

I recognize that eventually we will see that either ##a_0## (and ##a_1'## ) or ##a_1 ##(and ##a_0'##) must equal 0 for the solution to be finite, but that's at a later stage in the derivation. At this stage in the derivation, what's wrong with still assuming ##a_0 \neq 0## and ##a_1 \neq 0##??

I also recognize that I may be mucking things up due to staring at this for far too long..

Thanks!

I'm reading through Jackson's Classical Electrodynamics book and am working through the derivation of the Legendre polynomials. He uses this ##\alpha## term that seems to complicate the derivation more and is throwing me for a bit of a loop. Jackson assumes the solution is of the form:

Inserting this into the differential equation we need to solve,

we obtain:

He then says:

which I agree with. The issue I'm having is with the next statement:

First, in saying the two relations are equivalent, I assume he means that if ##a_0 \neq 0## then we have ##P(x)_{a_0 \neq 0} = P_{\alpha=0}(x) + P_{\alpha=1}(x)##

##= a_0 +a_1*x^1+a_2*x^2 +...## ##+## ##a_0'*x^1+a_1'*x^2+a_2'*x^3 +...##

whereas if ##a_1 \neq 0## then we have ##P(x)_{a_1 \neq 0} = P_{\alpha=0}(x) + P_{\alpha=-1}(x)##

##= a_0 +a_1*x^1+a_2*x^2 +...## ##+## ##a_0''*x^{-1}+a_1''+a_2''*x^1+...##

and, setting ##a''##=0 to avoid the potential blowing up at x=0, ##P(x)_{a_0 \neq 0}## is basically the same as ##P(x)_{a_1 \neq 0}##, since each can be expressed as an infinite series in the form of ##c_0+c_1*x^1+c_2*x^2+...##. Therefore, we can choose either ##a_0 \neq 0## or ##a_1 \neq 0##.

But then he says we can't have both ##a_0 \neq 0## and ##a_1 \neq 0##, which I don't quite follow. If they were both 0, we'd need ##\alpha \equiv 0 ## (to satisfy his eq 3.13) and the solution would be of the form ##a_0+a_1*x^1+a_2*x^2+...##. What's wrong with that at this point in the derivation?

I recognize that eventually we will see that either ##a_0## (and ##a_1'## ) or ##a_1 ##(and ##a_0'##) must equal 0 for the solution to be finite, but that's at a later stage in the derivation. At this stage in the derivation, what's wrong with still assuming ##a_0 \neq 0## and ##a_1 \neq 0##??

I also recognize that I may be mucking things up due to staring at this for far too long..

Thanks!