- #1

Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,990

- 48

I am reading Louis Rowen's book, "Ring Theory" (Student Edition) ...

I have a problem interpreting Rowen's notation in Section 1.1 Matrix Rings and Idempotents ...

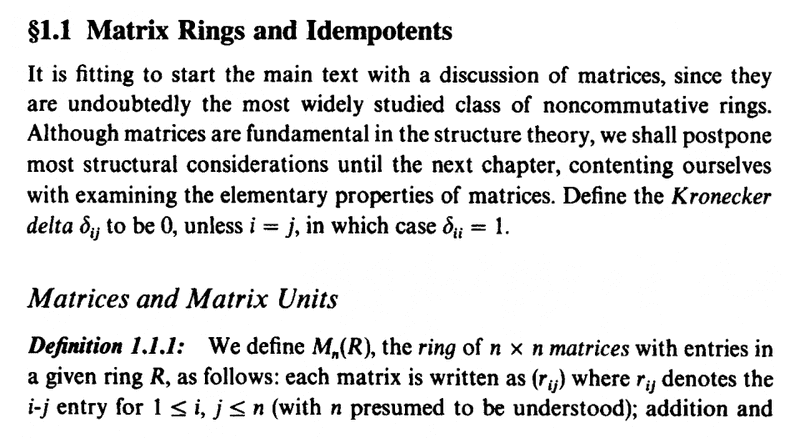

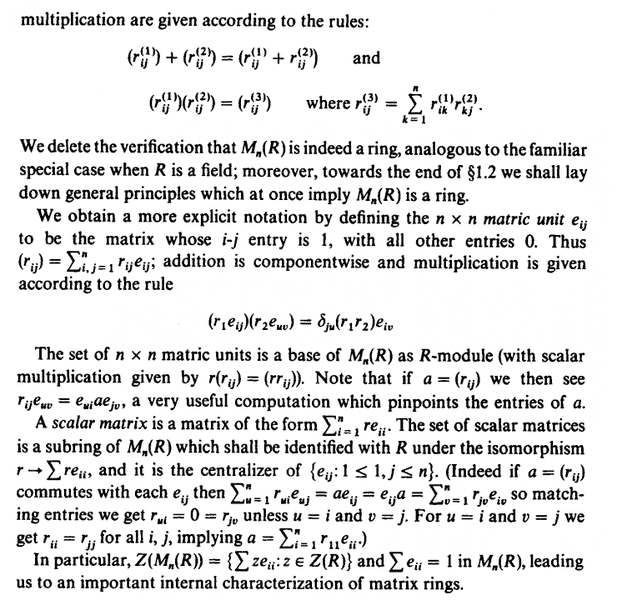

The relevant section of Rowen's text reads as follows:

In the above text from Rowen, we read the following:

" ... ... We obtain a more explicit notation by defining the ##n \times n## matric unit ##e_{ij}## to be the matrix whose ##i-j## entry is ##1##, with all other entries ##0##.

Thus ##( r_{ij} ) = \sum_{i,j =1}^n r_{ij} e_{ij}## ; addition is componentwise and multiplication is given according to the rule

##( r_1 e_{ij} ) ( r_2 e_{uv} ) = \delta_{ju} (r_1 r_2) e_{iv}##

... ... ... "

I am having trouble understanding the rule ##( r_1 e_{ij} ) ( r_2 e_{uv} ) = \delta_{ju} (r_1 r_2) e_{iv}## ... ...

What are ##r_1## and ##r_2## ... where exactly do they come from ...

Can someone please explain the rule to me ...?

To take a specific example ... suppose we are dealing with ##M_2 ( \mathbb{Z} )## and we have two matrices ...##P = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 3 \\ 5 & 4 \end{pmatrix}##and ##Q = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 3 & 3 \end{pmatrix}## ...In this specific case, what are ##r_1## and ##r_2## ... ... and how would the rule in question work ...?Hope someone can help ...

Peter

I have a problem interpreting Rowen's notation in Section 1.1 Matrix Rings and Idempotents ...

The relevant section of Rowen's text reads as follows:

In the above text from Rowen, we read the following:

" ... ... We obtain a more explicit notation by defining the ##n \times n## matric unit ##e_{ij}## to be the matrix whose ##i-j## entry is ##1##, with all other entries ##0##.

Thus ##( r_{ij} ) = \sum_{i,j =1}^n r_{ij} e_{ij}## ; addition is componentwise and multiplication is given according to the rule

##( r_1 e_{ij} ) ( r_2 e_{uv} ) = \delta_{ju} (r_1 r_2) e_{iv}##

... ... ... "

I am having trouble understanding the rule ##( r_1 e_{ij} ) ( r_2 e_{uv} ) = \delta_{ju} (r_1 r_2) e_{iv}## ... ...

What are ##r_1## and ##r_2## ... where exactly do they come from ...

Can someone please explain the rule to me ...?

To take a specific example ... suppose we are dealing with ##M_2 ( \mathbb{Z} )## and we have two matrices ...##P = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 3 \\ 5 & 4 \end{pmatrix}##and ##Q = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 3 & 3 \end{pmatrix}## ...In this specific case, what are ##r_1## and ##r_2## ... ... and how would the rule in question work ...?Hope someone can help ...

Peter

Attachments

Last edited: