Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Sheldon Axler's book: Measure, Integration & Real Analysis ... and I am focused on Chapter 2: Measures ...

I need help with the proof of Result 2.8 ...

Result 2.8 and its proof read as follows

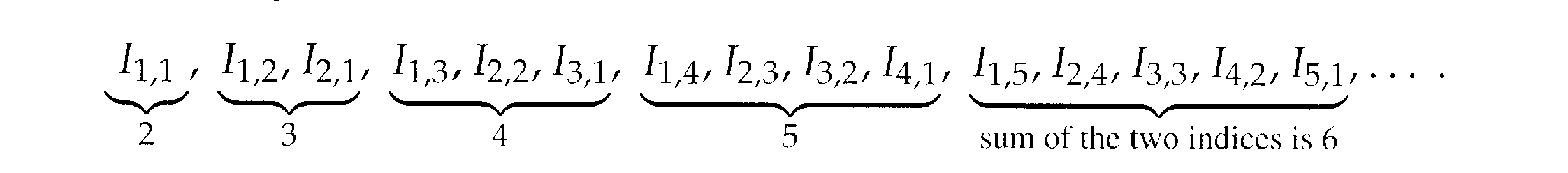

In the above text from Axler we read:"The doubly indexed collection of open intervals [math] \{ I_{ j, k } : j,k \in \mathbb{Z^+} \} [/math] can be rearranged into a sequence of open intervals whose union contains [math] \bigcup_{ k = 1 }^{ \infty} A_k [/math] as follows, where in step k (start with k =2, then k = 3,4,5 ... ) we adjoin the k-1 intervals whose indices add up to k :

Inequality 2.9 shows that the sum of the lengths listed above is less than or equal to [math] \epsilon + \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} |A_k| [/math]. Thus [math] | \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} A_k | \leq \epsilon + \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} |A_k| [/math] ... ..."

Inequality 2.9 shows that the sum of the lengths listed above is less than or equal to [math] \epsilon + \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} |A_k| [/math]. Thus [math] | \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} A_k | \leq \epsilon + \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} |A_k| [/math] ... ..."

i really do not understand what is going on here ... can someone explain why we are arranging or grouping the intervals [math] \{ I_{ j, k } : j,k \in \mathbb{Z^+} \} [/math] in this way and why exactly it follows that the sum of the lengths listed above is less than or equal to $ \epsilon + \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} |A_k| $ ...Hope someone can help,

Peter

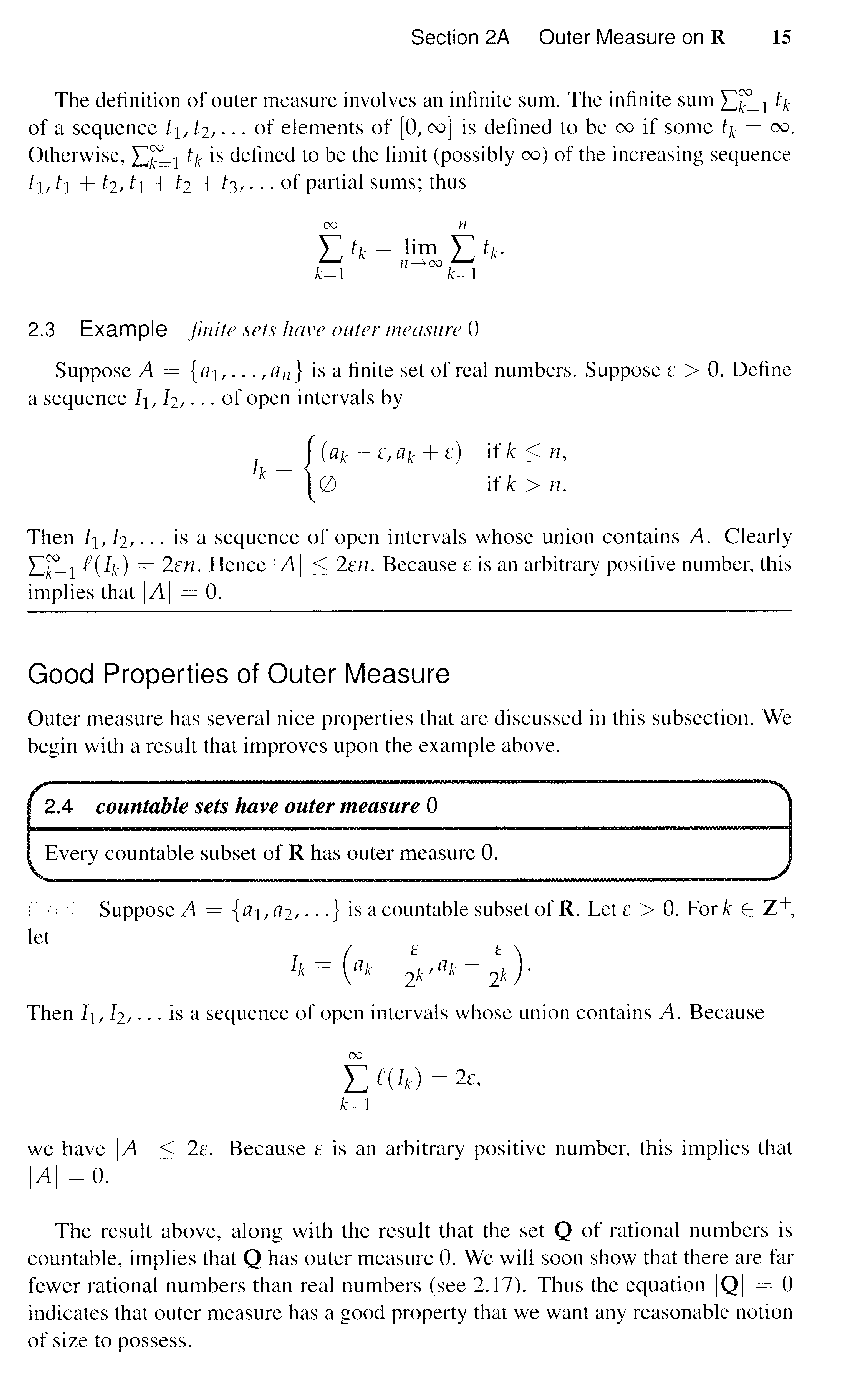

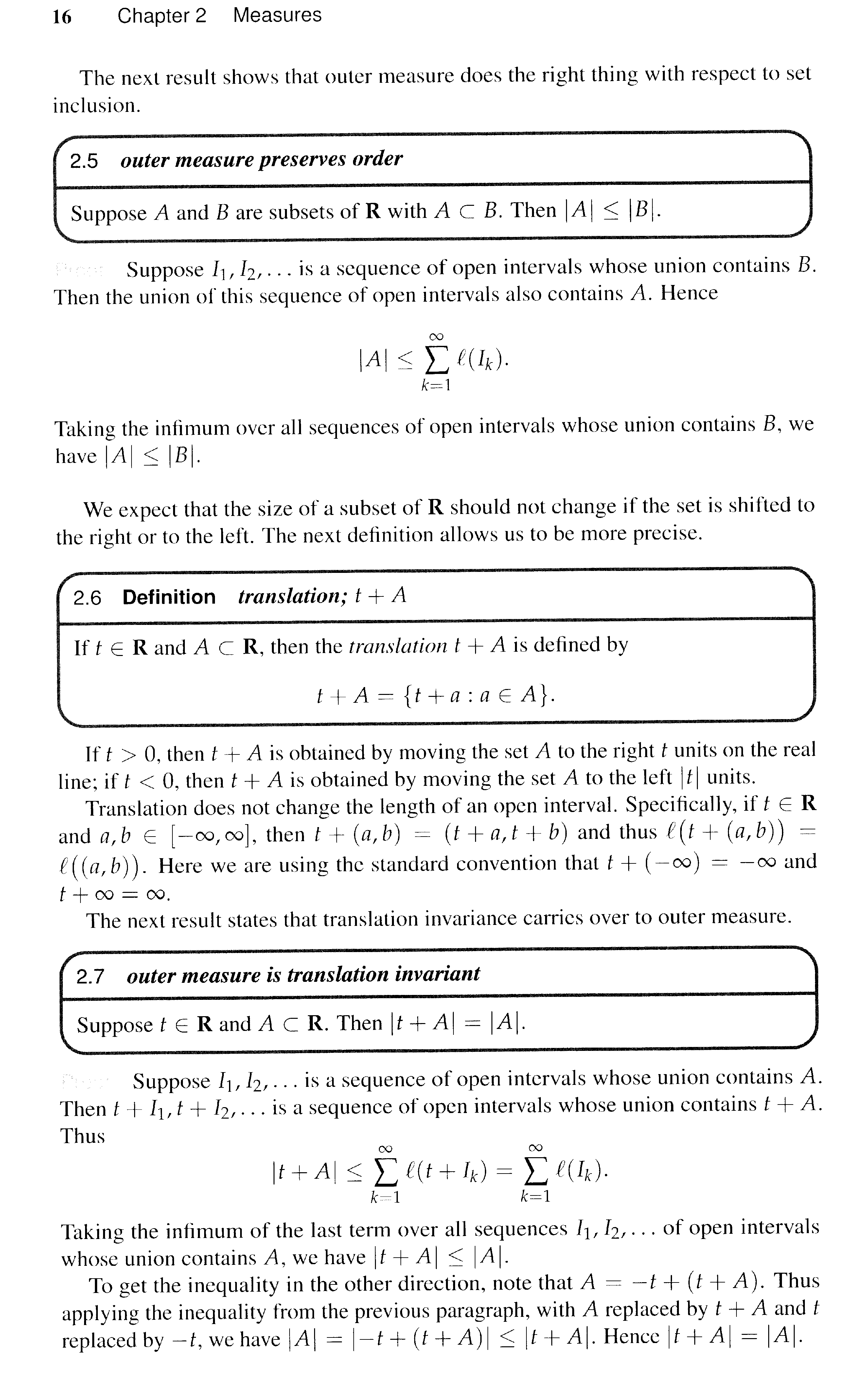

NOTE: so that readers of the above post will have enough contextual and notational information i am posting the start of Axler's Section @A on Outer Measure ... as follows:

Hope that helps Peter

I need help with the proof of Result 2.8 ...

Result 2.8 and its proof read as follows

In the above text from Axler we read:"The doubly indexed collection of open intervals [math] \{ I_{ j, k } : j,k \in \mathbb{Z^+} \} [/math] can be rearranged into a sequence of open intervals whose union contains [math] \bigcup_{ k = 1 }^{ \infty} A_k [/math] as follows, where in step k (start with k =2, then k = 3,4,5 ... ) we adjoin the k-1 intervals whose indices add up to k :

i really do not understand what is going on here ... can someone explain why we are arranging or grouping the intervals [math] \{ I_{ j, k } : j,k \in \mathbb{Z^+} \} [/math] in this way and why exactly it follows that the sum of the lengths listed above is less than or equal to $ \epsilon + \sum_{k=1}^{ \infty} |A_k| $ ...Hope someone can help,

Peter

NOTE: so that readers of the above post will have enough contextual and notational information i am posting the start of Axler's Section @A on Outer Measure ... as follows:

Hope that helps Peter

Last edited: