Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Sheldon Axler's book: Measure, Integration & Real Analysis ... and I am focused on Chapter 2: Measures ...

I need help with proving that the outer measure of an open interval, \mid (a, b) \mid = b - a

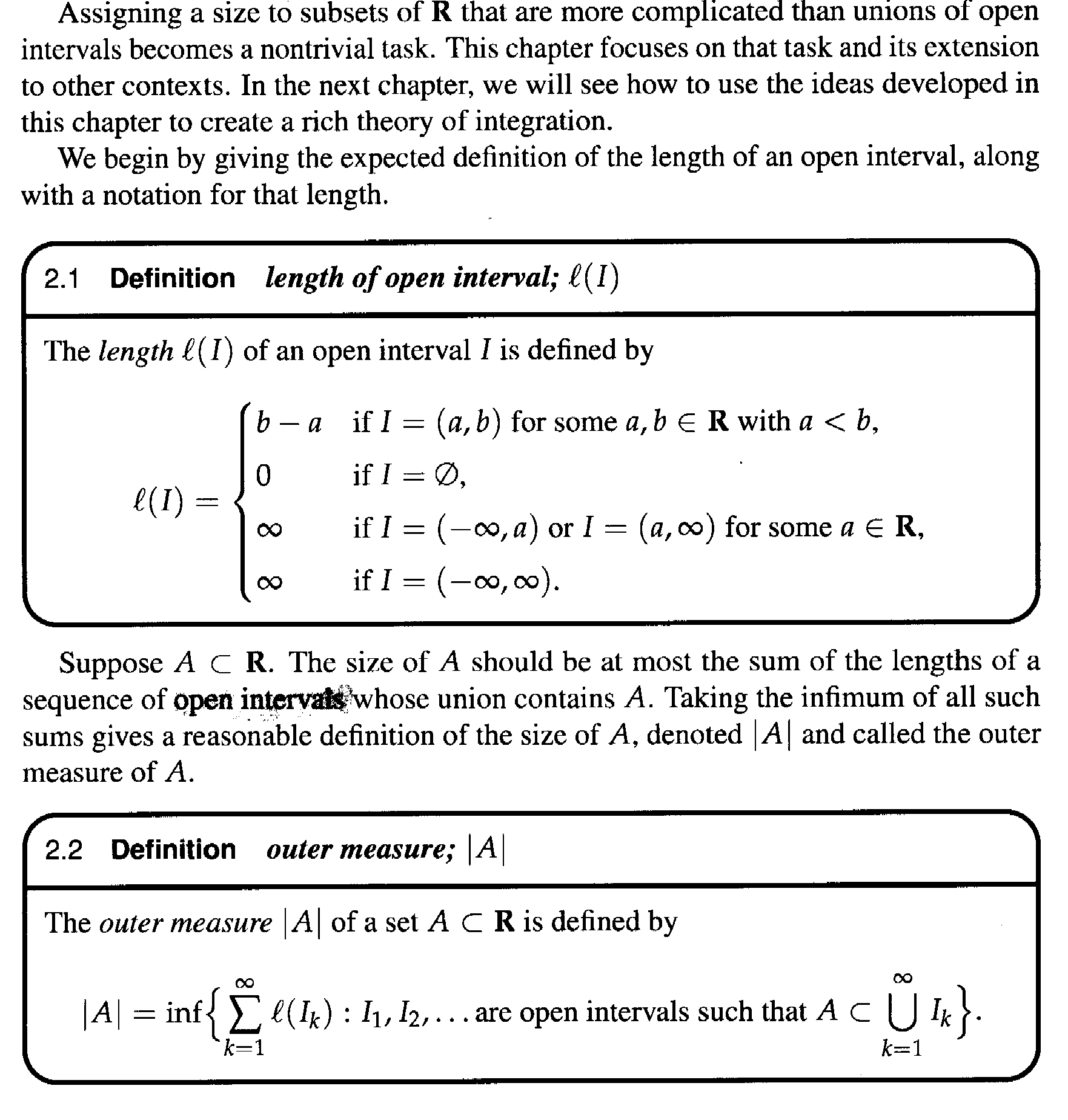

Axler's definitions of length and outer measure are as follows:

Can someone demonstrate rigorously that $$ \mid (a, b) \mid = b - a$$ ...

I know it seems intuitively obvious but how would you express a convincing and rigorous proof of the above result ...

Help will be much appreciated ... ...

Peter

I need help with proving that the outer measure of an open interval, \mid (a, b) \mid = b - a

Axler's definitions of length and outer measure are as follows:

Can someone demonstrate rigorously that $$ \mid (a, b) \mid = b - a$$ ...

I know it seems intuitively obvious but how would you express a convincing and rigorous proof of the above result ...

Help will be much appreciated ... ...

Peter

Last edited: