evinda

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,741

- 0

Hello! (Wave)

View attachment 5684

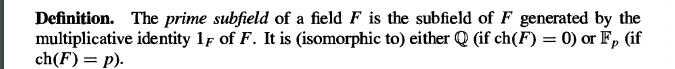

Could you explain to me why the prime subfield of any field $F$ could be isomorphic to $\mathbb{Q}$ ?

How do we find the prime subfield?

View attachment 5684

Could you explain to me why the prime subfield of any field $F$ could be isomorphic to $\mathbb{Q}$ ?

How do we find the prime subfield?