This may not cover all cases, but all the cases I can think of where one has to show that a function is well-defined is where a representative element of one of the items described in, or implied by, the function 'setup' plays a critical role in completing the definition. To be well-defined, it must be the case that the choice of the representative element doesn't give a different outcome.

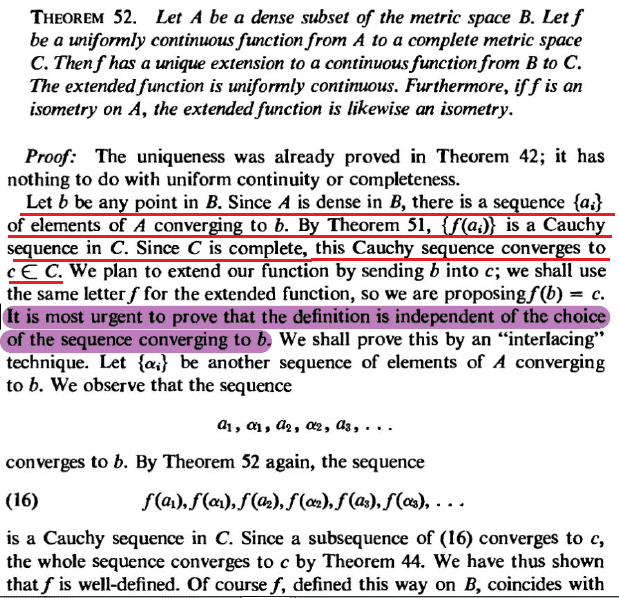

In the above case, we are defining the extended function, which maps each point in B to a unique point in C. We consider a point b in B, and consider the set S of all sequences in A whose limit is b. We then choose from out of S a representative element ##\{a_i\}##, and define ##f(b)## to be the limit in C of the sequence ##\{f(a_i)\}##. But we can imagine different choices of representative elements giving us different points for ##f(b)##. So we need to prove that doesn't happen - that if we choose any other sequence in S, applying the definition to that sequence will give us the same point.

Here is another example of definitions that need to be shown to be well-defined:

When working with https://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=AwrT4pQgRV5bT4EApBAL5gt.;_ylu=X3oDMTByb2lvbXVuBGNvbG8DZ3ExBHBvcwMxBHZ0aWQDBHNlYwNzcg--/RV=2/RE=1532933536/RO=10/RU=https%3a%2f%2fen.wikipedia.org%2fwiki%2fGroup_%28mathematics%29/RK=2/RS=Smc9UlHPVS1lTnSKLA6WLmMompE- in number theory, for any integer ##m## and a set of integers ##G## that is a group under the operation of addition, we define the 'm https://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=AwrT4pO6R15bXloAMSUL5gt.;_ylu=X3oDMTByb2lvbXVuBGNvbG8DZ3ExBHBvcwMxBHZ0aWQDBHNlYwNzcg--/RV=2/RE=1532934202/RO=10/RU=https%3a%2f%2fen.wikipedia.org%2fwiki%2fCoset/RK=2/RS=npPeviSyXRdl_ETg.HCbJavs0hE- of G', denoted by ##m+G##, as the set of integers ##\{m+g\ :\ g\in G\}##.

So if ##G=5\mathbb Z## and ##m=12## the coset ##m+G##, which is ##12 +5\mathbb Z## is the set ##\{...,-8,-3,2,7,12,17,...\}##. Note that this is identical to ##r+2\mathbb Z## for any ##r## in the coset. For instance it's identical to ##-8+5\mathbb Z## and to ##2+5\mathbb Z##. SO in our notation, the item before the ##+G## part is just a representative element of the coset.

We can then define an operation of addition between cosets of G by saying the sum of the cosets ##a+G## and ##b+G## is the coset ##(a+b)+G##.

But a and b are just representative elements of the two cosets being added, so we need to prove that using different representative elements doesn't give a different coset for the sum. For instance we need to show that

##(-8+52\mathbb Z) + (4+5\mathbb Z) ##, which is defined to be ##((-8+4)+5\mathbb Z) = -4+5\mathbb Z)##, is equal to

##(2+5\mathbb Z) + (-1+5\mathbb Z) ##, which is defined to be ##((-8+4)+5\mathbb Z) = 1+5\mathbb Z)##.

It is not hard to prove that that is the case, but it needs to be done.

It is often not easy to spot when a proof of well-definition is needed. When confronted with a new definition, one needs to scrutinise the steps taken in producing the defined item, to see if there is any implicit or explicit choice made in there. In the case of the OP, it's fairly straightforward, as we explicitly choose a single sequence from the set of all sequences that converge to b. In the coset case it's less obvious, because the notation ##-8+5\mathbb Z## makes it look like ##-8## has been specified, but in fact it is just part of the notation and what it refers to is just the set ##\{...,-8,-3,2,7,12,17,...\}##. The trick is to remember that sometimes choices are made in the notation that are not an intrinsic part of what is being defined. There is nothing special about -8 in the set ##\{...,-8,-3,2,7,12,17,...\}## and ##-8+5\mathbb Z## is just one of an infinite number of different possible ways of referring to it. ##-8+5\mathbb Z## is the same object as ##2+5\mathbb Z## so if we make any claim about that object, or a definition for some operation on it, we need to prove that the truth of the claim or the outcome of the definition does not depend on the choice of notation we make to refer to it.