bobby2k

- 126

- 2

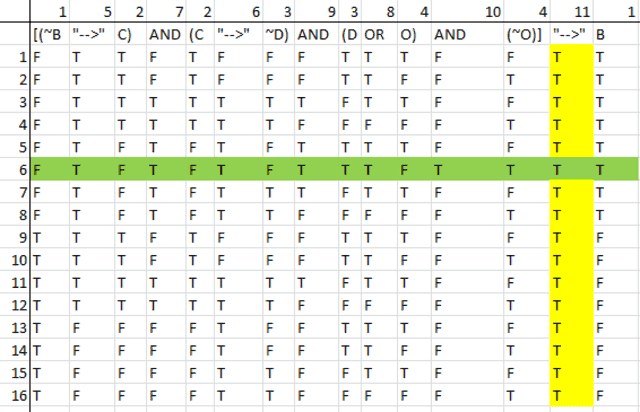

Please take a look at this proof:

The thing I do not get is how they can do it so fast. If I were to prove this using a truth table, I would have to use 16 rows, because of all the possibilities, however they seem to not have to take into account a lot of the possibilities when they prove this.

For me it looks like they have assumed that:

\negB→C is TRUE

C→\negD is TRUE

D\veeO is TRUE

\negO is TRU

But how can they just do this?

I made the truth table, am I correct to assume that the proof above, they only looked at row six in the truth table, many other possibilities were not considered? How can they just look away from these possibilities? Do you agree that they only considered row six in their proof?

The thing I do not get is how they can do it so fast. If I were to prove this using a truth table, I would have to use 16 rows, because of all the possibilities, however they seem to not have to take into account a lot of the possibilities when they prove this.

For me it looks like they have assumed that:

\negB→C is TRUE

C→\negD is TRUE

D\veeO is TRUE

\negO is TRU

But how can they just do this?

I made the truth table, am I correct to assume that the proof above, they only looked at row six in the truth table, many other possibilities were not considered? How can they just look away from these possibilities? Do you agree that they only considered row six in their proof?

Last edited: