mathmari

Gold Member

MHB

- 4,984

- 7

Hey!

(Wondering)

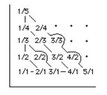

- Show that the set of all positive rational numbers is a countable set.

(Hint: Consider all points in the first quadrant of the plane of which the coordinates x and y are integers.) - Show that the union of a countable number of countable sets is a countable set.

- Let $x,y>0$. We write a positive rational $\frac{x}{y}$ at the point (x, y) in the plane in the first quadrant. Now we have to count these points, or not?

- Do we have to use induction here?

(Wondering)