chwala

Gold Member

- 2,833

- 426

Homework Statement:: See attached

Relevant Equations:: Ring Theory

Trying to go through my undergraduate notes on Ring Theory ( in appreciation to my Professor who opened me up to the beautiful World of Math)...anyways see attached...

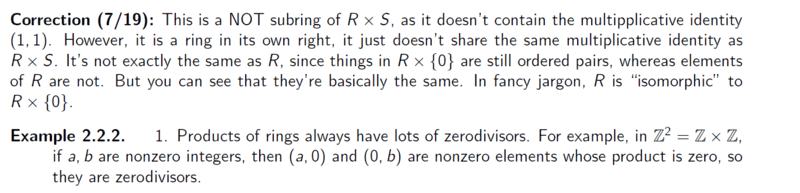

I need some clarity on the zero divisor. I am aware that we may have a left or right zero divisor where ##a## is an element in a ring ##R## and there exists a non zero ##x## in ##R## such that,

##ax=0##, now looking at the above example, 2.2.2 we have ##(a,0)⋅(0,b)=(a⋅0, 0⋅b)=(0,0)##, since product is equal to ##(0,0)## then we conclude that the elements are zero divisors. Now my question is, using the definition, ##ax=0##, and given that ##a,b## are elements in ##R##, then what would be our ##x?##

or are we supposed to say, consider ##(a,0)## as our ##a## and ##(0,b)## as our ##x##...cheers

I think i get it, ##(a,0)## is an element in ##R## and ##(0,b)## is the non zero element in ##R##. Right, let me continue with looking at the literature, i will ask questions in areas of doubt.

Relevant Equations:: Ring Theory

Trying to go through my undergraduate notes on Ring Theory ( in appreciation to my Professor who opened me up to the beautiful World of Math)...anyways see attached...

I need some clarity on the zero divisor. I am aware that we may have a left or right zero divisor where ##a## is an element in a ring ##R## and there exists a non zero ##x## in ##R## such that,

##ax=0##, now looking at the above example, 2.2.2 we have ##(a,0)⋅(0,b)=(a⋅0, 0⋅b)=(0,0)##, since product is equal to ##(0,0)## then we conclude that the elements are zero divisors. Now my question is, using the definition, ##ax=0##, and given that ##a,b## are elements in ##R##, then what would be our ##x?##

or are we supposed to say, consider ##(a,0)## as our ##a## and ##(0,b)## as our ##x##...cheers

I think i get it, ##(a,0)## is an element in ##R## and ##(0,b)## is the non zero element in ##R##. Right, let me continue with looking at the literature, i will ask questions in areas of doubt.

Last edited: