Discussion Overview

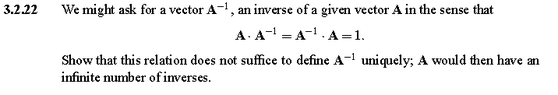

The discussion revolves around the uniqueness of inverse matrices, particularly in the context of vectors and their properties. Participants explore whether the equation \( A \cdot A^{-1} = A^{-1} \cdot A = I \) uniquely defines the inverse of a matrix or vector, and they examine various scenarios and assumptions related to this concept.

Discussion Character

- Debate/contested

- Technical explanation

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

- Some participants argue that the identity does not uniquely define the inverse, suggesting that there could be multiple inverses for a given matrix or vector.

- One participant proposes that if \( A \cdot B = I \) and \( A \cdot C = I \), then \( B \) must equal \( C \), implying uniqueness, but others challenge this reasoning.

- Another participant points out that if \( B \) is merely a one-sided inverse, it may not be unique, especially when \( A \) is non-square.

- There is a discussion about the nature of the dot product and its implications for defining inverses, with some questioning how the multiplication of vectors relates to the concept of inverses.

- One participant provides a specific example with vectors to illustrate that different vectors can yield the same dot product with a given vector, thus challenging the uniqueness claim.

- Concerns are raised about the validity of manipulating expressions involving inverses when the product may not be invertible.

- Some participants express confusion about the definitions and properties of inverses in the context of vectors versus matrices.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants do not reach a consensus on whether the identity uniquely defines the inverse. Multiple competing views remain, with some asserting uniqueness under certain conditions while others provide counterexamples and challenge the assumptions made.

Contextual Notes

There are limitations regarding the assumptions made about the nature of the matrices and vectors involved, particularly concerning their dimensions and whether they are singular or non-singular. The discussion also highlights the ambiguity in defining operations involving dot products and matrix multiplication.