SUMMARY

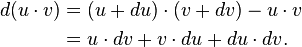

The forum discussion centers on the proof of the product rule using differentials as presented by Leibniz. It highlights the derivation of the product of functions through the limit of the difference function, specifically noting the equation d u·v = u·dv + v·du. The conversation emphasizes that the product of two differentials is negligible in the limit sense, leading to the conclusion that du·dv can be disregarded. The participants express a desire for clarity on the implications of using differentials in this context, particularly regarding the treatment of products of differentials in calculus.

PREREQUISITES

- Understanding of differential calculus

- Familiarity with Leibniz notation

- Knowledge of limits in calculus

- Concept of non-standard analysis

NEXT STEPS

- Study the derivation of the product rule in differential calculus

- Explore the concept of non-standard analysis in mathematics

- Learn about the implications of differentials in multivariable calculus

- Investigate the use of limits in calculus proofs

USEFUL FOR

Mathematics students, educators, and anyone interested in deepening their understanding of calculus, particularly in the context of differentials and the product rule.