caffeinemachine

Gold Member

MHB

- 799

- 15

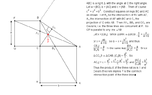

Let $ABC$ be a right angled triangle, where the right angle is at $A$.

Construct squares on $AC$, $AB$ and $BC$ as shown. Let $P$ be the point of intersection of $BK$ and $FC$ (Note that $P$ is not marked in the figure).

Then I conjecture that $AP$ is parallel to $BD$.View attachment 4630What I tried:By obsercing that $\Delta FBC\cong \Delta ABD$, we see that $\angle BAC=\angle BFC$.

Therefore, if $X$ is the point of intersection of $FC$ and $AD$, we see that $BFAX$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.This gives us that $AD\perp FC$, and similarly $BK\perp AE$. But I couldn't go any further.

Construct squares on $AC$, $AB$ and $BC$ as shown. Let $P$ be the point of intersection of $BK$ and $FC$ (Note that $P$ is not marked in the figure).

Then I conjecture that $AP$ is parallel to $BD$.View attachment 4630What I tried:By obsercing that $\Delta FBC\cong \Delta ABD$, we see that $\angle BAC=\angle BFC$.

Therefore, if $X$ is the point of intersection of $FC$ and $AD$, we see that $BFAX$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.This gives us that $AD\perp FC$, and similarly $BK\perp AE$. But I couldn't go any further.