zzzhhh

- 39

- 1

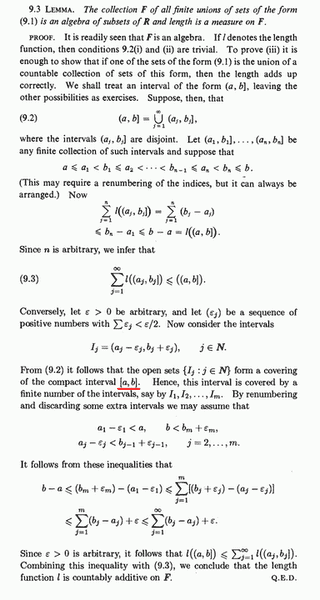

This question comes from the proof of Lemma 9.3 of Bartle's "The Elements of Integration and Lebesgue Measure" in page 97-98. This proof is shown as the image below.

Form (9.1) mentioned in the lemma is: (a,b], (-\infty,b], (a,+\infty), (-\infty,+\infty).

My question is: although I_j constructed in P98 is a bit fatter than (a_j,b_j], I doubt the assertion that the left endpoint a, and in turn the compact interval [a,b], is also covered by \{I_j\}, as the proof in the text claimed (I drew a red underline). Is my doubt correct (this means the text is incorrect), or point a can be proved to be covered by \{I_j\} (how)? Thanks!

PS: the establishment of the converse inequality does not need the coverage of the whole [a,b]. A small shrink, say [a+\epsilon,b], is sufficient to get the inequality.

Form (9.1) mentioned in the lemma is: (a,b], (-\infty,b], (a,+\infty), (-\infty,+\infty).

My question is: although I_j constructed in P98 is a bit fatter than (a_j,b_j], I doubt the assertion that the left endpoint a, and in turn the compact interval [a,b], is also covered by \{I_j\}, as the proof in the text claimed (I drew a red underline). Is my doubt correct (this means the text is incorrect), or point a can be proved to be covered by \{I_j\} (how)? Thanks!

PS: the establishment of the converse inequality does not need the coverage of the whole [a,b]. A small shrink, say [a+\epsilon,b], is sufficient to get the inequality.