mcastillo356

Gold Member

- 660

- 365

- Homework Statement

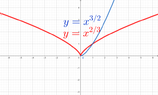

- Prove ##\lim{(x^{2/3})}## when ##x\rightarrow{0^{+}}## is 0

- Relevant Equations

- ##\forall{\epsilon>0}##, find ##\delta>0## such that ##0<x<\delta\Rightarrow{|f(x)|<\epsilon}##

Hi, PF

In a Spanish math forum I got this proof of a right hand limit:

"For a generic ##\epsilon>0##, in case the inequality is met, we have the following: ##|x^{2/3}|<\epsilon\Rightarrow{|x|^{2/3}}\Rightarrow{|x|<\epsilon^{3/2}}##. Therein lies the condition. If ##x>0##, then ##|x|=x##; therefore, if the following holds: ##0<x<\epsilon^{3/2}\Rightarrow{|f(x)|<\epsilon}##, eventually, we can state: ##\forall{\epsilon>0}\;\exists{\delta>0}## s.t. ##0<x<\delta\Rightarrow{|f(x)|<\epsilon}##. In conclusion, the ##\delta## sought is epsilon elevated to three means, ##\delta=\epsilon^{3/2}##."

What is your opinion? It's right, yes, but... Something tells me it shall be improved.

Love

I'm going to click, no preview.

In a Spanish math forum I got this proof of a right hand limit:

"For a generic ##\epsilon>0##, in case the inequality is met, we have the following: ##|x^{2/3}|<\epsilon\Rightarrow{|x|^{2/3}}\Rightarrow{|x|<\epsilon^{3/2}}##. Therein lies the condition. If ##x>0##, then ##|x|=x##; therefore, if the following holds: ##0<x<\epsilon^{3/2}\Rightarrow{|f(x)|<\epsilon}##, eventually, we can state: ##\forall{\epsilon>0}\;\exists{\delta>0}## s.t. ##0<x<\delta\Rightarrow{|f(x)|<\epsilon}##. In conclusion, the ##\delta## sought is epsilon elevated to three means, ##\delta=\epsilon^{3/2}##."

What is your opinion? It's right, yes, but... Something tells me it shall be improved.

Love

I'm going to click, no preview.