James50

- 18

- 1

I'm just trying to think of a qualititive solution to the following thought experiment:

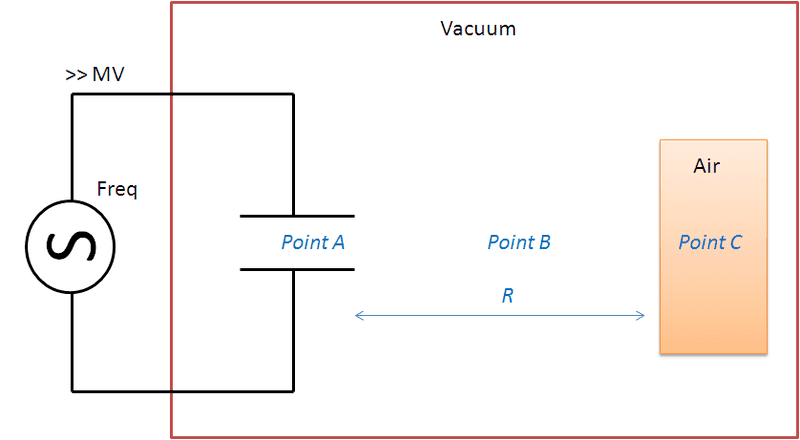

I have an RF source of very large voltage driving a signal towards point A (say, a capacitor or a dipole antenna). The source itself is not really part of this experiment, but I just want a sinusoidal voltage across point A. Ignore any effects in the wiring/waveguides due to high voltage.

Now, assume the electric field across point A is greater than the electric breakdown of air (which is around 3 MV/m), but below the breakdown of a vacuum. Say around 1 GV/m.

Now, presume in the far field (so that R >> 2*wavelength), a pocket of air exists. Ignore any boundary effects from vacuum to air.

At both point A and point B, we expect just normal, far field radiation with E proporational to 1/distance. At point C, assume the electric field is greater than the breakdown of air, ie greater than 3 MV/m.

What happens at point C? As I see it, there are a few options (I use spark and breakdown interchangably):

1) All locations in point C have an oscillating, continuous spark, depending on the instantaneous electric field it is experiencing... First it sparks upwards, then downwards, then upwards, etc, throughout the volume of the air. This to me seems unlikely - I just can't picture it.

2) Only the very first "bit" of air that the RF hits experiences an oscillating, continuous spark, depending on the instantaneous electric field at that location. This spark acts in anti-phase to the incoming RF and therefore cancels the large RF field for the rest of the air pocket. I can't see this either - I have no reason to believe it would act in anti-phase, or even that the wavelength of radiation that the spark would emit would equal the wavelength of the incoming RF.

3) All locations in point C have, at differing times, a quasi-random sparking, that is almost uncorrelated with the electric field. Each individual spark has an interfering effect on other sparks, leading to a non-predicatable pattern of breakdowns.

4) Only the very first "bit" of air that the RF hits experiences an quasi-random sparking, which interferes with the electric field in the rest of the air (not allowing sparking)

5) Nothing happens in the air - the oscillating nature of the RF field does allow enough time for a plasma to be created and therefore there is no sparking.

6) All of the above? Something else? Is option 5) highly likely for a high frequency RF signal, but not likely for a low frequency RF signal?I suspect for a high enough frequency (whatever that may be) signal, nothing will happen, as the plasma will not be able to form before the electric field flips. For a lower frequency signal (again, whatever that may be) I really am not sure. Lightning, for example, is caused by a steady build up of static voltage, which is discharged in a single strike, but this doesn't dicharge the entire cloud/storm front, only the bit in a localised area (i.e. you get more than one strike in a storm). This would suggest, perhaps, option 3).

So, any ideas?

I have an RF source of very large voltage driving a signal towards point A (say, a capacitor or a dipole antenna). The source itself is not really part of this experiment, but I just want a sinusoidal voltage across point A. Ignore any effects in the wiring/waveguides due to high voltage.

Now, assume the electric field across point A is greater than the electric breakdown of air (which is around 3 MV/m), but below the breakdown of a vacuum. Say around 1 GV/m.

Now, presume in the far field (so that R >> 2*wavelength), a pocket of air exists. Ignore any boundary effects from vacuum to air.

At both point A and point B, we expect just normal, far field radiation with E proporational to 1/distance. At point C, assume the electric field is greater than the breakdown of air, ie greater than 3 MV/m.

What happens at point C? As I see it, there are a few options (I use spark and breakdown interchangably):

1) All locations in point C have an oscillating, continuous spark, depending on the instantaneous electric field it is experiencing... First it sparks upwards, then downwards, then upwards, etc, throughout the volume of the air. This to me seems unlikely - I just can't picture it.

2) Only the very first "bit" of air that the RF hits experiences an oscillating, continuous spark, depending on the instantaneous electric field at that location. This spark acts in anti-phase to the incoming RF and therefore cancels the large RF field for the rest of the air pocket. I can't see this either - I have no reason to believe it would act in anti-phase, or even that the wavelength of radiation that the spark would emit would equal the wavelength of the incoming RF.

3) All locations in point C have, at differing times, a quasi-random sparking, that is almost uncorrelated with the electric field. Each individual spark has an interfering effect on other sparks, leading to a non-predicatable pattern of breakdowns.

4) Only the very first "bit" of air that the RF hits experiences an quasi-random sparking, which interferes with the electric field in the rest of the air (not allowing sparking)

5) Nothing happens in the air - the oscillating nature of the RF field does allow enough time for a plasma to be created and therefore there is no sparking.

6) All of the above? Something else? Is option 5) highly likely for a high frequency RF signal, but not likely for a low frequency RF signal?I suspect for a high enough frequency (whatever that may be) signal, nothing will happen, as the plasma will not be able to form before the electric field flips. For a lower frequency signal (again, whatever that may be) I really am not sure. Lightning, for example, is caused by a steady build up of static voltage, which is discharged in a single strike, but this doesn't dicharge the entire cloud/storm front, only the bit in a localised area (i.e. you get more than one strike in a storm). This would suggest, perhaps, option 3).

So, any ideas?