ali PMPAINT

- 44

- 8

- Homework Statement

- described on picture

- Relevant Equations

- described on picture

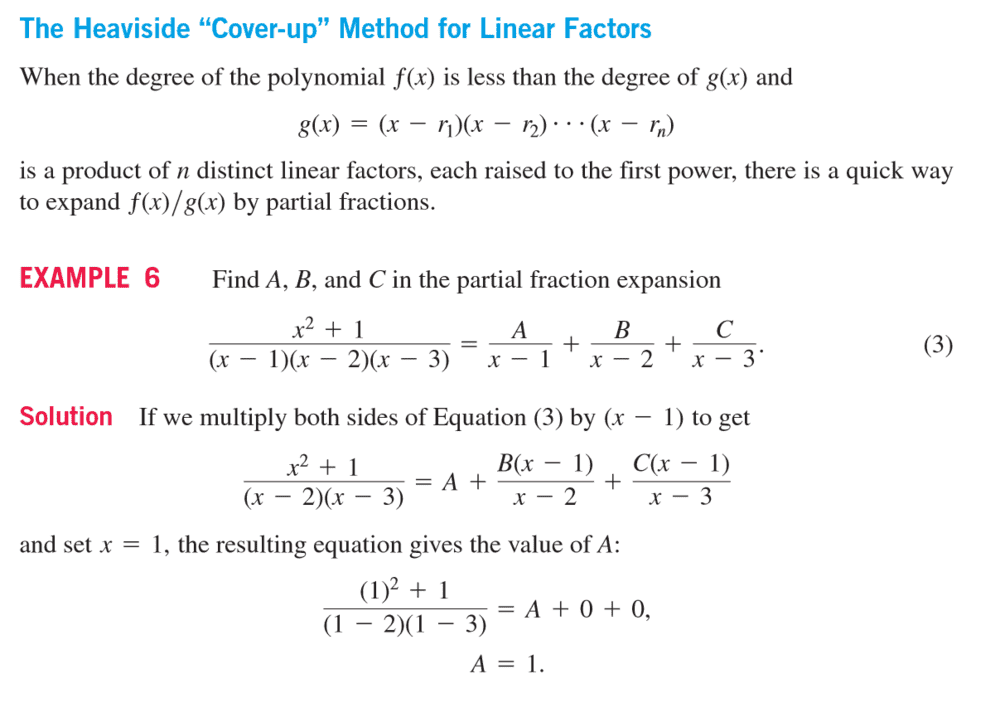

So, Heavside's method confused me, I mean, but we can't divide by zero, can we?

So, my mind sees it as cheating, and to multiply both sides by zero to cancel zeros, and for the example above(from Thomas Calulus), when x = 1, before you multiply by x-1(=0), you get: 2/0=A/0+B/-1+c/-2, and I think you get the point where I am confused, where am I misunderstanding Heavside's method?

So, my mind sees it as cheating, and to multiply both sides by zero to cancel zeros, and for the example above(from Thomas Calulus), when x = 1, before you multiply by x-1(=0), you get: 2/0=A/0+B/-1+c/-2, and I think you get the point where I am confused, where am I misunderstanding Heavside's method?