Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Hugo D. Junghenn's book: "A Course in Real Analysis" ...

I am currently focused on Chapter 9: "Differentiation on \mathbb{R}^n"

I need some help with the proof of Proposition 9.1.2 ...

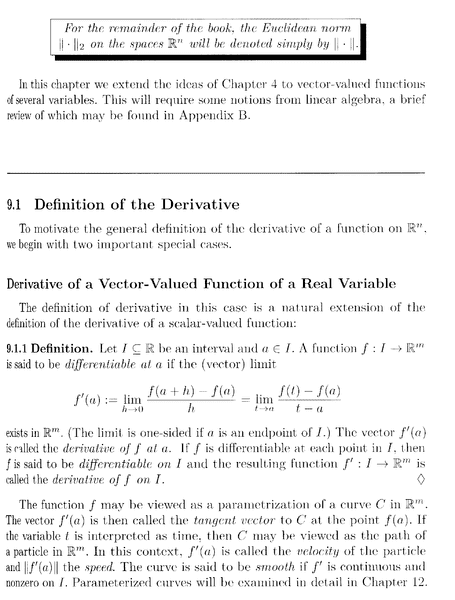

Proposition 9.1.2 and the preceding relevant Definition 9.1.1 read as follows:

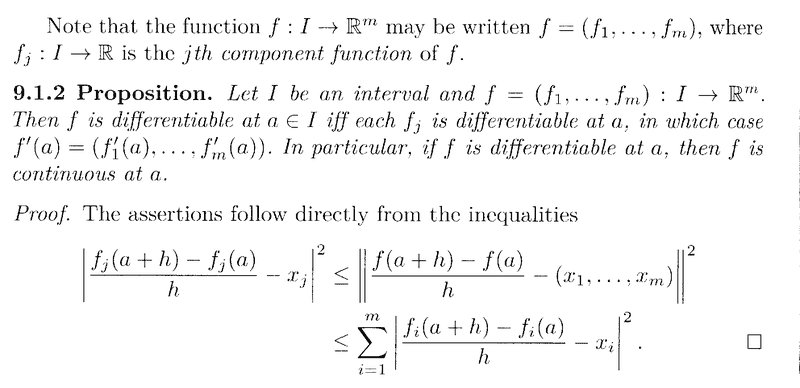

In the above text from Junghenn we read the following:

" ... ... The assertions follow directly from the inequalities

## \left\vert \frac{f_j ( a + h ) - f_j (a)}{ h } - x_j \right\vert^2 \le \left\| \frac{ f( a + h ) - f(a) }{ h } - ( x_1, \ ... \ ... \ , x_m ) \right\|^2####\le \sum_{ i = 1 }^m \left\vert \frac{f_j ( a + h ) - f_j (a)}{ h } - x_j \right\vert^2## ...

... ... "

Can someone please show why the above inequalities hold true ... and further how they lead to the proof of Proposition 9.1.2 ... ...Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

I am currently focused on Chapter 9: "Differentiation on \mathbb{R}^n"

I need some help with the proof of Proposition 9.1.2 ...

Proposition 9.1.2 and the preceding relevant Definition 9.1.1 read as follows:

In the above text from Junghenn we read the following:

" ... ... The assertions follow directly from the inequalities

## \left\vert \frac{f_j ( a + h ) - f_j (a)}{ h } - x_j \right\vert^2 \le \left\| \frac{ f( a + h ) - f(a) }{ h } - ( x_1, \ ... \ ... \ , x_m ) \right\|^2####\le \sum_{ i = 1 }^m \left\vert \frac{f_j ( a + h ) - f_j (a)}{ h } - x_j \right\vert^2## ...

... ... "

Can someone please show why the above inequalities hold true ... and further how they lead to the proof of Proposition 9.1.2 ... ...Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

Attachments

Last edited: