Spin One

- 4

- 0

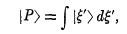

When one wants to represent a general ket in a basis consisting of eigenkets each attributed to an eigenvalue in a range, say from a to b, why does one take the integral of said kets from a to b w.r.t. the eigenvalues?

I understand that the integral here plays a role analogous to a sum in the case where a general ket is expressed in terms of eigenkets belonging to discrete eigenvalues, but I don't understand why each vector is multiplied by an infinitesimal change near the eigenvalue it belongs to. Interpreting this integral as the limit of a sum we get:

[P>=Σ[ξ>Δξ (lim.Δξ→0)

where I do not understand the role of Δξ.

I understand that the integral here plays a role analogous to a sum in the case where a general ket is expressed in terms of eigenkets belonging to discrete eigenvalues, but I don't understand why each vector is multiplied by an infinitesimal change near the eigenvalue it belongs to. Interpreting this integral as the limit of a sum we get:

[P>=Σ[ξ>Δξ (lim.Δξ→0)

where I do not understand the role of Δξ.