Calculuser said:

First of all, I would like to thank you in advance for the reply before my further inquiry. I have a question in mind regarding my way of thinking that needs to be confirmed or corrected if I am wrong.

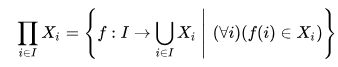

What is the role of (\forall{i}))(f(i)\in{X_i}) statement in the set in question?

It specifies the element. In general, a notation ##M:=\{\,a \in S\,|\,P(a) \text{ true }\,\}## reads: "The set of all elements ##a## from ##S##, which additionally satisfy property ##P(a)##. The part ##\in S## can be omitted, if it is clear which set we are talking about, or substituted by a description of ##S## as in our example. Also the part ##\text{ true }## is normally omitted, as it is implied by the location within the definition in ##\,|\,\ldots \,\}##. Here are all necessary conditions listed, which make the ##a## elements of ##M## instead of just elements of ##S##. In our case we have:##

- ##M \triangleq \Pi_{\iota \in I}X_\iota##

- ##a \triangleq f##

- ##S \triangleq \text{The set of all functions }I \longrightarrow \bigcup_{\iota \in I}X_\iota##

- ##P(a) \triangleq f\text{ can only assign an element from the set }X_\iota \text{ for every }\iota \in I \Longleftrightarrow (\forall{\iota})(f(\iota)\in{X_\iota})##

I removed that part from the set definition in question and then pondered what it would mean only with the rest. It would mean nothing but a list of functions defined as I → \bigcup_{i\in{I}}X_i. Therefore, if there existed a function, say f_1(i) with I = \{a,b\} and X_a, X_b, such that it mapped all elements to arbitrary element(s) under the condition of f_1(a), f_1(b) \in X_a, which in my opinion makes the existence of X_b immaterial. That is why I thought we need to modify that definition by adding the statement in the question above that necessitates the selection of an element from X_b.

?

In other words, I thought of functions as choice functions that picks out elemets from each X_i.

Yes. And you cannot pick from ##X_j## at the ##i-##th position if ##i\neq j\,.##

E.g. If we have ##X_1=\{\,a,b\,\}\, , \,X_2=\{\,\text{ trunk },\text{ branch },\text{ leaf }\,\}##, then ##f(1)=b\, , \,f(2)=\text{ trunk }## is allowed, and since we have finitely many indices, i.e. ##|I|=2\,,## we may write ##f \triangleq (b,\text{trunk})##. Elements ##g(1)=b\, , \,g(2)=a## or ##h(1)=\text{leaf}\, , \,h(2)=\text{trunk}## are not allowed in the direct product. If we removed the ##P(a) \text{ true }## part of the definition, as you suggested, the functions ##g## and ##h## would be allowed. Thus the part ##P(a) \triangleq

Is there any missing point above?

I don't know, because I did not understand what you wrote. I hope I have answered it anyway.

Additionally, If we write the expression as \prod_{i\in{I}}X_i=(x_1,x_2,...)=\{f_1,f_3,f_4,...\}, then how can we say that ordered tuples defined by (...) are equivalent to a set defined by \{...\}? They are different notations. Do we just ignore that?

First of all, this will only work for countable index sets ##I##, not for index sets like ##I=\mathbb{R}##. For the arguments sake, let us assume ##I=\mathbb{N}## here! You are right, that ##(x_1=f(1),x_2=f(2),\ldots ) ## and ##\{\,f(1),f(2),\ldots\,\}## are different objects: the first is an

element of the Cartesian product and the second is a

set of function values, so they cannot be equal.

However, with ##f(i)=x_i \in X_i##, any permutation won't change the situation significantly, i.e. it doesn't matter if we consider an ordered tuple or a set of value. Again we have the problem with uncountable index sets. In case of ##I=\mathbb{N}## we have a nice ordering and can talk about tuples. But what to do if ##I=\mathbb{R}\,?## To match this general situation, direct products are defined without the necessity of an ordering, namely as functions ##f## instead of tuples. The distinction between e.g. ##X_1\times X_2## and ##X_2 \times X_1## isn't important, as long as we do not mix them: ##\{\,f \, : \,\{\,1,2\,\} \longrightarrow X_1 \cup X_2\,|\,f(1)\in X_1 \wedge f(2)\in X_2\,\}## avoids this confusion. Sure, in case ##I=\mathbb{N}## we normally list ##(x_1,x_2,\ldots)## since it is convenient and there is no need to artificially apply a permutation of the indices. But you are right, the formal definition doesn't consider any ordering.

For short: If ##I## has a natural ordering, we normally use it in our notation, if it has not, then we can't.

Another example is how we right functions in general. E.g. we are used to write ##f(n)=\frac{1}{n}## as ##(1,\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{4},\ldots)## but at the same time would never try this for ##f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\; , \;x\in \mathbb{R}_{>0}\,.##