Nipon Waiyaworn

Hello everybody. I have to prove the fallowing theorem:

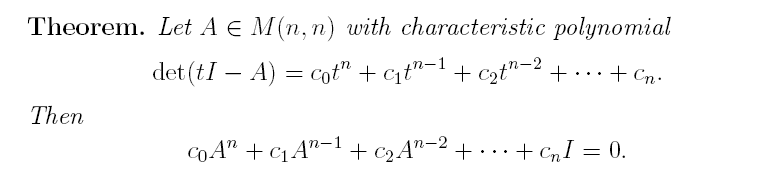

The Cayley-Hamilton Theorem

help me please...

The Cayley-Hamilton Theorem

help me please...

The discussion centers on proving the Cayley-Hamilton Theorem, which states that every square matrix satisfies its own characteristic polynomial. Participants emphasize the importance of understanding minimal polynomials and generalized eigenspaces. Key strategies include proving the theorem for non-defective matrices first and then extending the proof to defective matrices using upper triangular matrices or perturbation methods. The discussion references "Linear Algebra Done Wrong" by Treil for a comprehensive walkthrough and highlights the significance of non-commutative algebra in the proof process.

PREREQUISITESMathematicians, students of linear algebra, and anyone interested in advanced matrix theory and the applications of the Cayley-Hamilton Theorem.

mathman said:What happens if you substitute A for t in the determinant equation?

I found Chris Bernhart's document but I don't understand, How is inverse of I-tA indicated by power series in t with coefficients M(n,n)?fresh_42 said:How far did you get? As far as I can see, it is not as simple as it might appear, will say it takes several steps. What do you know about minimal polynomials and generalized eigenspaces? Have you done a google search? I'm almost sure that the proof can be found online.

StoneTemplePython said:You might want to start simple here.

assume the field is ##\mathbb C## (or if all eigenvalues are real, and the matrix is real, then you can use ##\mathbb R##)

Now assume the matrix is not defective (i.e. the ##n## x ##n## matrix has ##n## linearly independent eigenvectors.) Can you prove Cayley Hamilton for the non-defective case?

lavinia said:The field does not need to be the complex numbers. One needs the eigen values to be distinct when one extends the scalar field to be the complex numbers. For instance the real matrix ##\begin{pmatrix}0&-1\\1&0\end{pmatrix}## has characteristic polynomial ##(t-i)(t+i)##.

I was just trying to say that you can extend scalars and get to the situation that you are talking about. I thought your point was that using the complex numbers allows the characteristic polynomial to be factored into linear factors. If these factors are distinct as you want to assume in order to "start simple" then the theorem follows immediately.StoneTemplePython said:I'm not sure what you're trying to get at here. My suggestion to OP was to start simple. To my mind this means diagonalizable matrices in an algebraically closed filed... ##\mathbb C## is very natural in this context.

I have no idea what you're referring to when you say that "one needs the eigenvalues to be distinct" when using complex numbers. The example you give is skew Hermitian which is a normal matrix, and non-defective per spectral theorem. I can think of plenty of larger ##n## x ##n## permutation matrices that have repeated eigenvalues (i.e. algebraic multiplicity ##\gt 1##). Yet these too are non-defective because they are a special case of a unitary and hence normal.

After dealing with diagonalizable matrices, the natural next step for OP is to look at Cayley Hamilton in context of defective matrices, which is a bit more work.

There are of course other approaches, but I'm inclined to start simple and build which is what LADW does.

Thank you ขอบคุณครับStoneTemplePython said:You might want to start simple here.

assume the field is ##\mathbb C## (or if all eigenvalues are real, and the matrix is real, then you can use ##\mathbb R##)

Now assume the matrix is not defective (i.e. the ##n## x ##n## matrix has ##n## linearly independent eigenvectors.) Can you prove Cayley Hamilton for the non-defective case?

Then to extend this to defective matrices, you either cleverly work with upper triangular matrices (which has some subtleties), or perturb the eigenvalues by very small amounts, and show that your matrix is approximated up to any arbitrary level of precision by a diagonalizable one... and re-use the argument from before.

There's a nice walk-though in chapter 9 of Linear Algebra Done Wrong.

https://www.math.brown.edu/~treil/papers/LADW/book.pdf

I'd recommend working through the whole book at some point -- its very well done.

I guess you could also use formal power series and classical adjoints... but that seems rather unpleasant.

fresh_42 said:What about fields which are not of characteristic zero?

I only thought that the nice density argument, which I really liked, fails in these cases, and a field extension would be of no help. But I'm not sure whether there's a topological workaround. The Zariski topology comes to mind for algebraic equations. In my book it's done with generalized eigenspaces and I assumed that the theorem works for any field, although I haven't checked it. (If authors assume certain conditions on the characteristic, it's usually somewhere else in the book.)lavinia said:I think one can use the structure theorem for modules of finite type over a principal ideal domain. This works for any vector space but seems a bit abstracted away from the original question.

fresh_42 said:I only thought that the nice density argument, which I really liked, fails in these cases, and a field extension would be of no help. But I'm not sure whether there's a topological workaround. The Zariski topology comes to mind for algebraic equations. In my book it's done with generalized eigenspaces and I assumed that the theorem works for any field, although I haven't checked it. (If authors assume certain conditions on the characteristic, it's usually somewhere else in the book.)

I'm afraid I don't know what you mean. I think that a topological argument doesn't work in a finite case. It's just that I don't claim anything if topology is involved, and as long as I'm not sure. Greub's proof is only linear algebra. He shows that the minimal polynomial of a transformation divides the characteristic polynomial ... and as I thought, his overall assumption at the beginning of the chapter is characteristic zero. But where would it be needed for Cayley-Hamilton?lavinia said:I would be very interested to see how this might work.

mathwonk said:http://alpha.math.uga.edu/%7Eroy/80006c.pdf