Discussion Overview

The discussion centers around the Laplace operator, specifically its definition as the dot product of gradient vector operators and its relationship to second derivatives. Participants explore the implications of this definition and the notation involved, questioning how the dot product leads to a second derivative rather than a squared first derivative.

Discussion Character

- Technical explanation

- Debate/contested

- Conceptual clarification

Main Points Raised

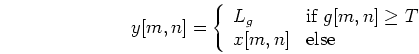

- One participant questions how the dot product of gradient operators results in a second derivative, suggesting it should be represented as the del operator squared.

- Another participant explains that the dot product of the gradient operators can be expressed as the sum of second partial derivatives, which leads to the second derivative.

- Some participants propose that the notation used for the gradient operator can be misleading, as it suggests a multiplication that does not directly correspond to traditional multiplication.

- There is a challenge regarding whether the result should be interpreted as the first derivative squared, with some participants asserting that it is indeed the second derivative.

- A later reply emphasizes that the gradient operator must operate on a function to have meaning, indicating that the notation is a matter of convention rather than a strict mathematical operation.

- Concerns are raised about the abuse of notation, with one participant noting that the gradient operator should not be considered in isolation from the function it operates on.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the interpretation of the Laplace operator and the notation involved. There is no consensus on whether the dot product should be viewed as yielding a second derivative or if it should be considered as a squared first derivative.

Contextual Notes

The discussion highlights potential ambiguities in notation and the need for clarity when discussing operators in calculus. Some participants point out that the formal definitions and operations may not align with intuitive understandings.