Discussion Overview

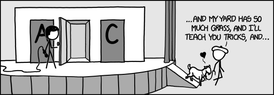

The discussion revolves around variations of the Monty Hall problem, exploring how different setups affect the probability of winning a car. Participants compare scenarios with different numbers of doors and the implications of choosing a door initially versus not. The conversation includes theoretical reasoning and personal experiences with teaching the concept.

Discussion Character

- Debate/contested

- Conceptual clarification

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

- Some participants question whether variations of the Monty Hall problem with different numbers of doors are fundamentally the same, expressing confusion about why probabilities differ.

- One participant argues that the initial choice of a door is crucial to the Monty Hall problem, as it influences the subsequent actions of the host, Monty Hall.

- Another participant emphasizes that if there are only two doors remaining after one is removed, the probability of winning becomes 50/50, contrasting with the original problem's setup.

- A participant suggests that the Monty Hall problem can be better understood through simulations or by scaling the number of doors to illustrate the probabilities more clearly.

- Some participants share personal experiences of teaching the problem and the common misconceptions that arise, noting that even with demonstrations, some individuals remain unconvinced.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the significance of the initial choice in the Monty Hall problem and whether the variations presented are equivalent. The discussion remains unresolved, with multiple competing perspectives on the implications of different setups.

Contextual Notes

Participants highlight the importance of the rules governing the door-opening process and the initial choice, suggesting that these factors significantly influence the outcome probabilities. There is an acknowledgment of the complexity and counterintuitive nature of the problem, which may lead to misunderstandings.