Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Hugo D. Junghenn's book: "A Course in Real Analysis" ...

I am currently focused on Chapter 9: "Differentiation on ##\mathbb{R}^n##"

I need some help with the proof of Proposition 9.2.3 ...

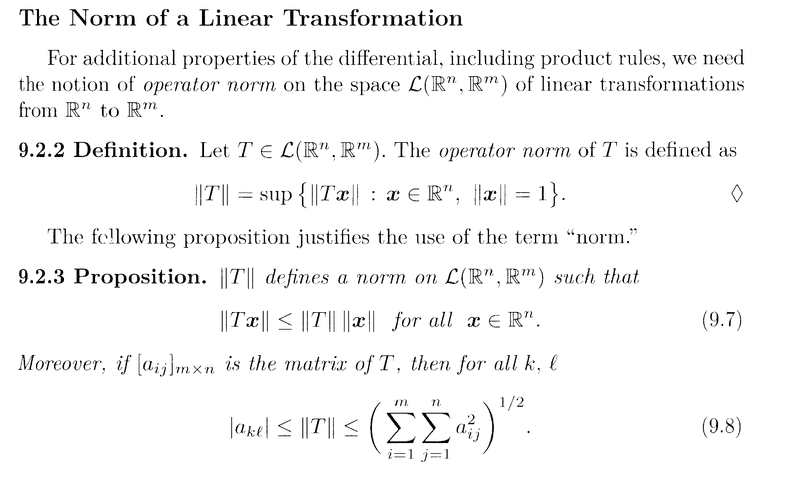

Proposition 9.2.3 and the preceding relevant Definition 9.2.2 read as follows:

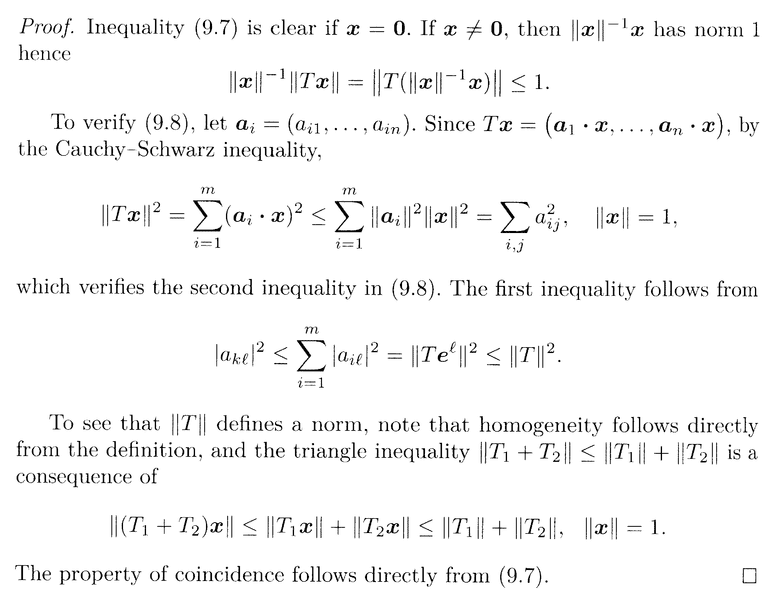

In the above proof we read the following:

" ... ... If ##\mathbf{x} \neq \mathbf{0} \text{ then } \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x}## has a norm ##1##, hence

##\| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \| T \mathbf{x} \| = \| T ( \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x} ) \| \le 1## ... ... "

Now I know that ##T( c \mathbf{x} ) = c T( \mathbf{x} )##

... BUT ...

... how do we know that this works "under the norm sign" ...

... that is, how do we know ...##\| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \| T \mathbf{x} \| = \| T ( \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x} ) \|##... and further ... how do we know that ...##\| T ( \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x} ) \| \le 1##

Help will be appreciated ...

Peter

I am currently focused on Chapter 9: "Differentiation on ##\mathbb{R}^n##"

I need some help with the proof of Proposition 9.2.3 ...

Proposition 9.2.3 and the preceding relevant Definition 9.2.2 read as follows:

In the above proof we read the following:

" ... ... If ##\mathbf{x} \neq \mathbf{0} \text{ then } \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x}## has a norm ##1##, hence

##\| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \| T \mathbf{x} \| = \| T ( \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x} ) \| \le 1## ... ... "

Now I know that ##T( c \mathbf{x} ) = c T( \mathbf{x} )##

... BUT ...

... how do we know that this works "under the norm sign" ...

... that is, how do we know ...##\| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \| T \mathbf{x} \| = \| T ( \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x} ) \|##... and further ... how do we know that ...##\| T ( \| \mathbf{x} \|^{-1} \mathbf{x} ) \| \le 1##

Help will be appreciated ...

Peter