- 287

- 268

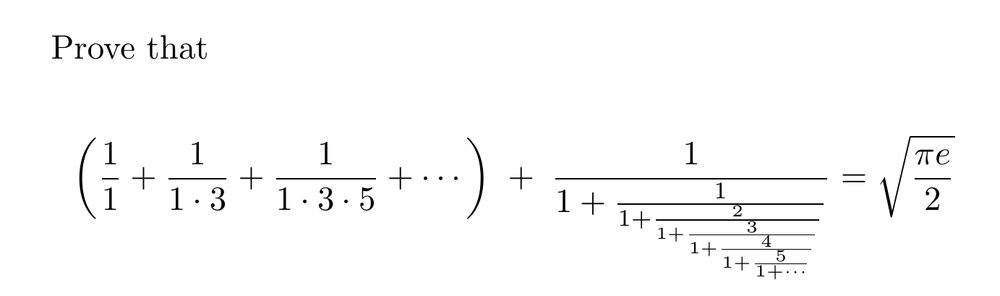

A while ago I decided to figure out how to prove one of Ramanujan’s formulas. I feel this is the sort of thing every mathematician should try at least once.

I picked the easiest one I could find:

Hardy called it one of the “least impressive”. Still, it was pretty interesting: it turned out to be a puzzle within a puzzle! It has an easy outer layer which one can solve using standard ideas in calculus, and a tougher inner core which requires more cleverness - but still, nothing beyond calculus.

Read more and learn how to prove this formula here:

I picked the easiest one I could find:

Hardy called it one of the “least impressive”. Still, it was pretty interesting: it turned out to be a puzzle within a puzzle! It has an easy outer layer which one can solve using standard ideas in calculus, and a tougher inner core which requires more cleverness - but still, nothing beyond calculus.

Read more and learn how to prove this formula here: