EE18

- 112

- 13

Misplaced Homework Thread

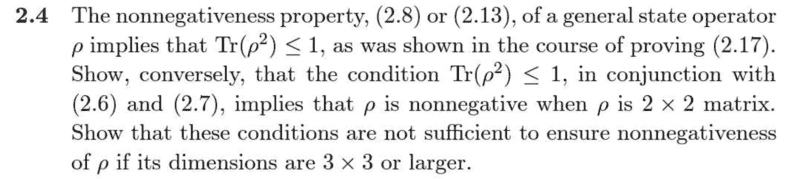

I am trying to solve Problem 2.4 in Ballentine:

I note in my attempt below to what (2.6) and (2.7) refer.

My attempt thus far is as follows:

A ##2 \times 2## state operator can be represented in a particular orthonormal ##\beta = \{\phi_i\}## as below, where we have enforced trace normalization (2.6) and self-adjointness (2.7) (and have yet to enforce nonnegativeness),

$$[\rho]_{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix}

a & b \\

b^* & (1-a)

\end{bmatrix}$$

Now enforcing ##Tr{\rho^2}## and using the basis independence of the trace we obtain

$$Tr{\rho^2} = Tr{[\rho]_{\beta}^2} = Tr{ \begin{bmatrix}

a & b \\

b^* & (1-a)

\end{bmatrix}^2} = a^2 +2|b|^2+ (1-a)^2 \leq 1$$

with ##a \in \mathbb{R}##.

Now for an arbitrary ##u## in our space we may expand ##u = \sum_i c_i {\phi_i}## so we can immediately compute

$$(u,\rho u) = \begin{bmatrix}

c_1^* & c_2^*

\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}

a & b \\

b^* & (1-a)

\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}

c_1 \\ c_2

\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}

c_1^* & c_2^*

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

ac_1 + bc_2 \\ b^*c_1+(1-a)c_2 \end{bmatrix}$$

$$=c_1^*(ac_1 + bc_2)+ c_2^*(b^*c_1+(1-a)c_2) = |{c_1}|^2a +2\textrm{Re}(c_1^*c_2b) + (1-a)^2|{c_2}|^2$$

but I can't seem to see how to go further here. It seems like I have to use my aforementioned inequality but I can't see how. Any help would be greatly appreciated.

I note in my attempt below to what (2.6) and (2.7) refer.

My attempt thus far is as follows:

A ##2 \times 2## state operator can be represented in a particular orthonormal ##\beta = \{\phi_i\}## as below, where we have enforced trace normalization (2.6) and self-adjointness (2.7) (and have yet to enforce nonnegativeness),

$$[\rho]_{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix}

a & b \\

b^* & (1-a)

\end{bmatrix}$$

Now enforcing ##Tr{\rho^2}## and using the basis independence of the trace we obtain

$$Tr{\rho^2} = Tr{[\rho]_{\beta}^2} = Tr{ \begin{bmatrix}

a & b \\

b^* & (1-a)

\end{bmatrix}^2} = a^2 +2|b|^2+ (1-a)^2 \leq 1$$

with ##a \in \mathbb{R}##.

Now for an arbitrary ##u## in our space we may expand ##u = \sum_i c_i {\phi_i}## so we can immediately compute

$$(u,\rho u) = \begin{bmatrix}

c_1^* & c_2^*

\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}

a & b \\

b^* & (1-a)

\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}

c_1 \\ c_2

\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}

c_1^* & c_2^*

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

ac_1 + bc_2 \\ b^*c_1+(1-a)c_2 \end{bmatrix}$$

$$=c_1^*(ac_1 + bc_2)+ c_2^*(b^*c_1+(1-a)c_2) = |{c_1}|^2a +2\textrm{Re}(c_1^*c_2b) + (1-a)^2|{c_2}|^2$$

but I can't seem to see how to go further here. It seems like I have to use my aforementioned inequality but I can't see how. Any help would be greatly appreciated.