Saitama

- 4,244

- 93

Problem:

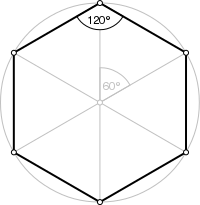

Given four non-zero vectors $\vec{a},\vec{b},\vec{c}$ and $\vec{d}$, the vectors $\vec{a},\vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$ are coplanar but not collinear pair by pair and $\vec{d}$ is not coplanar with vectors $\vec{a},\vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$ and $(\widehat{\vec{a}\vec{b}})=(\widehat{\vec{b}\vec{c}})=\frac{\pi}{3}, (\widehat{\vec{d}\vec{a}})=\alpha, (\widehat{\vec{d}\vec{b}})=\beta$, then prove that $(\widehat{\vec{d}\vec{c}})=\arccos(\cos\beta-\cos\alpha)$.

$\widehat{\vec{a}\vec{b}}$ denotes the angle between two vectors.

Attempt:

I have the following:

$$\hat{a}\cdot\hat{b}=\hat{b}\cdot\hat{c}=\frac{1}{2}$$

$$\hat{d}\cdot\hat{a}=\cos\alpha$$

$$\hat{d}\cdot\hat{b}=\cos\beta$$

Subtracting the above two equations, I get

$$\hat{d}\cdot (\hat{b}-\hat{a})=\cos\beta-\cos\alpha$$

I somehow need to show that $\hat{c}=\hat{b}-\hat{a}$ but I don't see how. I notice that $\vec{b}$ is the angle bisector of $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{c}$ but I am not sure if that helps.

Any help is appreciated. Thanks!

Given four non-zero vectors $\vec{a},\vec{b},\vec{c}$ and $\vec{d}$, the vectors $\vec{a},\vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$ are coplanar but not collinear pair by pair and $\vec{d}$ is not coplanar with vectors $\vec{a},\vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$ and $(\widehat{\vec{a}\vec{b}})=(\widehat{\vec{b}\vec{c}})=\frac{\pi}{3}, (\widehat{\vec{d}\vec{a}})=\alpha, (\widehat{\vec{d}\vec{b}})=\beta$, then prove that $(\widehat{\vec{d}\vec{c}})=\arccos(\cos\beta-\cos\alpha)$.

$\widehat{\vec{a}\vec{b}}$ denotes the angle between two vectors.

Attempt:

I have the following:

$$\hat{a}\cdot\hat{b}=\hat{b}\cdot\hat{c}=\frac{1}{2}$$

$$\hat{d}\cdot\hat{a}=\cos\alpha$$

$$\hat{d}\cdot\hat{b}=\cos\beta$$

Subtracting the above two equations, I get

$$\hat{d}\cdot (\hat{b}-\hat{a})=\cos\beta-\cos\alpha$$

I somehow need to show that $\hat{c}=\hat{b}-\hat{a}$ but I don't see how. I notice that $\vec{b}$ is the angle bisector of $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{c}$ but I am not sure if that helps.

Any help is appreciated. Thanks!