psie

- 315

- 40

- TL;DR

- Let ##\Omega\subset\mathbb R^n##. Consider the space ##C_c(\Omega)## of continuous, compactly supported functions equipped with the ##L^p## norm. Then in my lecture notes it is claimed the completion of this space is ##L^p(\Omega)##. I'm trying to verify to myself that this is indeed the case by the definition given below.

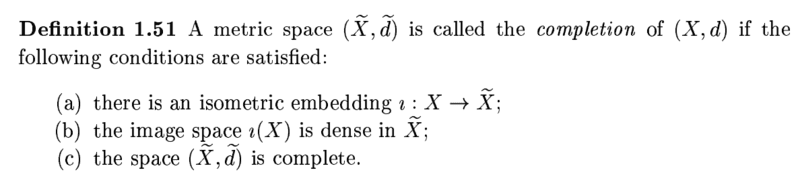

Consider the attached definition of completion of a metric space.

It has already been stated in my notes that ##L^p(\Omega)## equipped with ##\lVert\cdot\rVert_p## is a Banach space, hence complete. So (c) is satisfied. Also, there is a theorem that states that ##C_c(\Omega)## is a dense subset of ##L^p(\Omega)##. But I'm still having trouble verifying (a) and (b) in the definition. How could I construct a function between these metric spaces such that it is an isometry and its image is dense? What troubles me is that ##L^p(\Omega)## is a set of equivalence classes of functions, and hence the inclusion map ##i:C_c(\Omega)\to L^p(\Omega)## defined by ##f\mapsto f## would maybe not work.

It has already been stated in my notes that ##L^p(\Omega)## equipped with ##\lVert\cdot\rVert_p## is a Banach space, hence complete. So (c) is satisfied. Also, there is a theorem that states that ##C_c(\Omega)## is a dense subset of ##L^p(\Omega)##. But I'm still having trouble verifying (a) and (b) in the definition. How could I construct a function between these metric spaces such that it is an isometry and its image is dense? What troubles me is that ##L^p(\Omega)## is a set of equivalence classes of functions, and hence the inclusion map ##i:C_c(\Omega)\to L^p(\Omega)## defined by ##f\mapsto f## would maybe not work.