Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

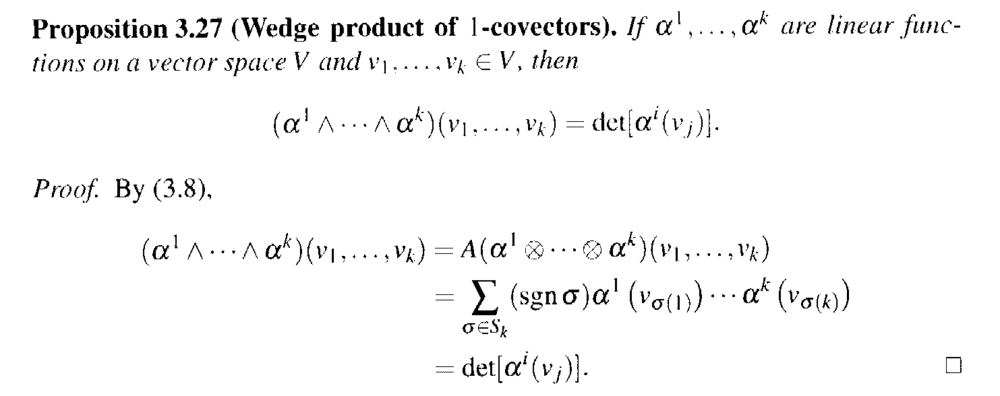

In Loring W. Tu's book: "An Introduction to Manifolds" (Second Edition) ... Proposition 3.27 reads as follows:

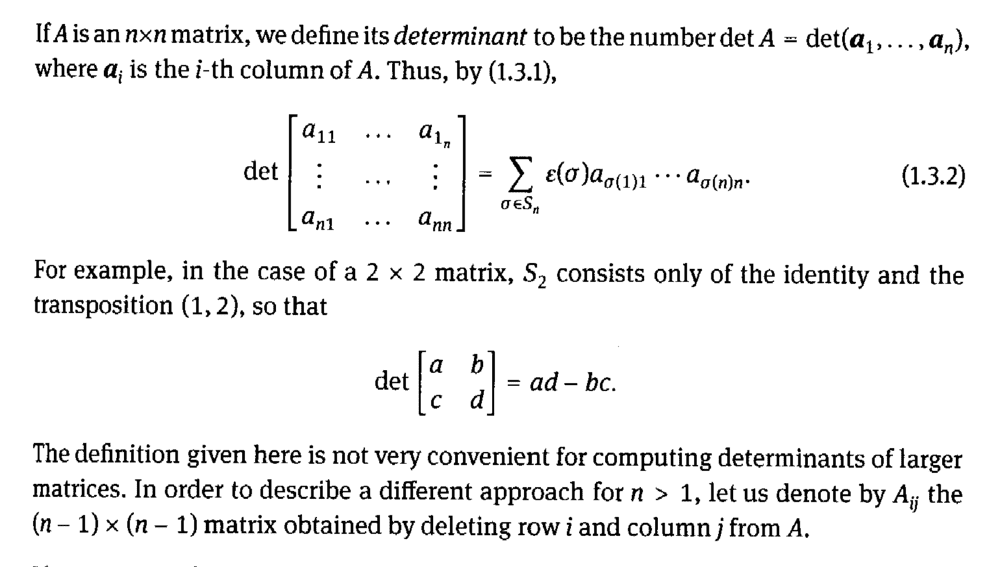

The above proposition gives the wedge product of k linear functions as a determinant ...Walschap in his book: "Multivariable Calculus and Differential Geometry" gives the definition of a determinant as follows:

From Tu's proof above we can say that ...

##\text{det} [ \alpha^i ( v_j ) ]####= \text{det} \begin{bmatrix} \alpha^1 ( v_1 ) & \alpha^1 ( v_2 ) & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \alpha^1 ( v_k ) \\ \alpha^2 ( v_1 ) & \alpha^2 ( v_2 ) & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \alpha^2 ( v_k ) \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ \alpha^3 ( v_1 ) & \alpha^3 ( v_2 ) & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \alpha^3 ( v_k ) \end{bmatrix}####= \sum_{ \sigma \in S_k } ( \text{ sgn } \sigma ) \alpha^1 ( v_{ \sigma (1) } ) \cdot \cdot \cdot \alpha^k ( v_{ \sigma (k) } )##Thus Tu is indicating that the column index ##j## is permuted ... that is we permute the rows of the determinant matrix ...But in the definition of the determinant given by Walschap we have##\text{det} \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & \cdot \cdot \cdot & a_{ 1n } \\ \cdot & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \cdot \\ a_{n1} & \cdot \cdot \cdot & a_{ nn } \end{bmatrix}####= \sum_{ \sigma \in S_n } \varepsilon ( \sigma ) a_{ \sigma (1) 1 } \cdot \cdot \cdot a_{ \sigma (n) n }##Thus Walschap is indicating that the row index ##i## is permuted ... that is we permute the columns of the determinant matrix ... in contrast to Tu who indicates that we permute the rows of the determinant matrix ...Can someone please reconcile these two approaches ... do we get the same answer to both ...?

Clarification of the above issues will be much appreciated ... ...

Peter

The above proposition gives the wedge product of k linear functions as a determinant ...Walschap in his book: "Multivariable Calculus and Differential Geometry" gives the definition of a determinant as follows:

From Tu's proof above we can say that ...

##\text{det} [ \alpha^i ( v_j ) ]####= \text{det} \begin{bmatrix} \alpha^1 ( v_1 ) & \alpha^1 ( v_2 ) & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \alpha^1 ( v_k ) \\ \alpha^2 ( v_1 ) & \alpha^2 ( v_2 ) & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \alpha^2 ( v_k ) \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ \alpha^3 ( v_1 ) & \alpha^3 ( v_2 ) & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \alpha^3 ( v_k ) \end{bmatrix}####= \sum_{ \sigma \in S_k } ( \text{ sgn } \sigma ) \alpha^1 ( v_{ \sigma (1) } ) \cdot \cdot \cdot \alpha^k ( v_{ \sigma (k) } )##Thus Tu is indicating that the column index ##j## is permuted ... that is we permute the rows of the determinant matrix ...But in the definition of the determinant given by Walschap we have##\text{det} \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & \cdot \cdot \cdot & a_{ 1n } \\ \cdot & \cdot \cdot \cdot & \cdot \\ a_{n1} & \cdot \cdot \cdot & a_{ nn } \end{bmatrix}####= \sum_{ \sigma \in S_n } \varepsilon ( \sigma ) a_{ \sigma (1) 1 } \cdot \cdot \cdot a_{ \sigma (n) n }##Thus Walschap is indicating that the row index ##i## is permuted ... that is we permute the columns of the determinant matrix ... in contrast to Tu who indicates that we permute the rows of the determinant matrix ...Can someone please reconcile these two approaches ... do we get the same answer to both ...?

Clarification of the above issues will be much appreciated ... ...

Peter

Attachments

Last edited: