etotheipi

A unit vector, ##\frac{\vec{v}}{|\vec{v}|}##, has dimensions of ##\frac{L}{L} = 1##, i.e. it is dimensionless. It has magnitude of 1, no units.

For a physical coordinate system, the coordinate functions ##x^i## have some units of length, e.g. ##\vec{x} = (3\text{cm})\hat{x}_1 + (6\text{cm})\hat{x}_2##. For instance, the axes might arbitrarily be labelled with values in "centimetres": however this choice itself is not too important since there is a one-to-one correspondence between the values of any given length measured in two different units.

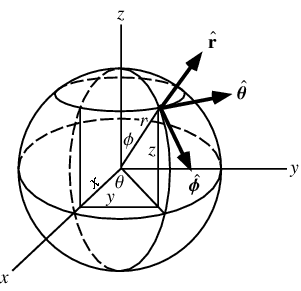

We often draw the unit vectors inside the Euclidian space, like this:

However, if the unit vectors are dimensionless, why does it make sense to draw them on the diagram? That is to say, how do you judge how long a length of a "vector of magnitude 1 (dimensionless)" is?

For a physical coordinate system, the coordinate functions ##x^i## have some units of length, e.g. ##\vec{x} = (3\text{cm})\hat{x}_1 + (6\text{cm})\hat{x}_2##. For instance, the axes might arbitrarily be labelled with values in "centimetres": however this choice itself is not too important since there is a one-to-one correspondence between the values of any given length measured in two different units.

We often draw the unit vectors inside the Euclidian space, like this:

However, if the unit vectors are dimensionless, why does it make sense to draw them on the diagram? That is to say, how do you judge how long a length of a "vector of magnitude 1 (dimensionless)" is?

Last edited by a moderator: