deuteron

- 64

- 14

- TL;DR

- .

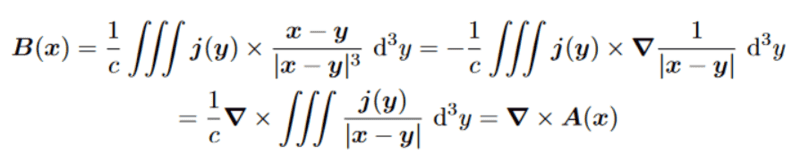

We have motivated the derivation of the vector potential in the following way:

However, I cannot understand where the ##-## sign in the second equality came from. I thought that it was because the gradient was with respect to the ##y##-variable, and then using the product rule one could explain the transition to the last expression, but in that case ##\nabla_{\vec y}\times\vec j(\vec y)## would have to be zero, which I am not really sure is necessarily true; and in that case I would again not understand how a ##\nabla_{\vec y}## would become a ##\nabla_{\vec x}##, since at ##\nabla\times \vec A(\vec x)## I assume ##\nabla## must be acting on the ##\vec x##

That's why I don't see how the left and right hand sides of the third, fourth, and possibly the fifts ##=## signs are equal to each other, can someone please help me?

However, I cannot understand where the ##-## sign in the second equality came from. I thought that it was because the gradient was with respect to the ##y##-variable, and then using the product rule one could explain the transition to the last expression, but in that case ##\nabla_{\vec y}\times\vec j(\vec y)## would have to be zero, which I am not really sure is necessarily true; and in that case I would again not understand how a ##\nabla_{\vec y}## would become a ##\nabla_{\vec x}##, since at ##\nabla\times \vec A(\vec x)## I assume ##\nabla## must be acting on the ##\vec x##

That's why I don't see how the left and right hand sides of the third, fourth, and possibly the fifts ##=## signs are equal to each other, can someone please help me?