- 3,372

- 465

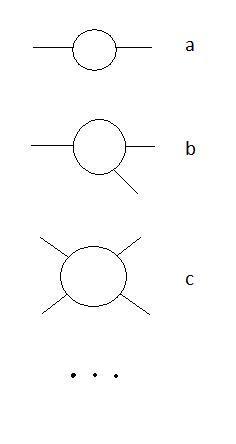

I wanted to ask, about the ##6##-dimensional ##\phi ^3 ## theory...

The Lagrangian is:

$$ L = \frac{1}{2} (\partial \phi)^2 - c \phi - \frac{m^2}{2} \phi^2 + \frac{g}{3!} \phi^3$$

When I want to draw all the 1-loop 1PI diagrams, should I make something like these:

?

The Lagrangian is:

$$ L = \frac{1}{2} (\partial \phi)^2 - c \phi - \frac{m^2}{2} \phi^2 + \frac{g}{3!} \phi^3$$

When I want to draw all the 1-loop 1PI diagrams, should I make something like these:

?