- 37,398

- 14,233

HEK VI: On the Dearth of Galilean Analogs in Kepler and the Exomoon Candidate Kepler-1625b I

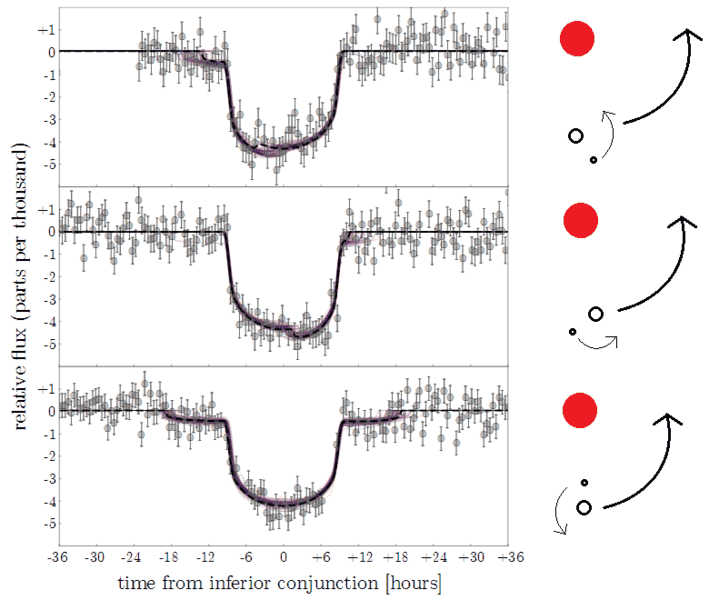

The authors looked for signals of potential moons in the Kepler transit data. There is some weak evidence that a group of smaller moons exists, but the measurements are not accurate enough to pin that down on a star-by-star level. One particular planet, however, Kepler-1625b, has very curious features in all three observed transits. The Hubble telescope will observe the next transit in October this year.

If it is a moon, then the parent planet probably has 10 Jupiter masses while being a bit smaller than Jupiter, and the moon has Neptune size.

The star is probably quite old already and leaving the main sequence.

Wikipedia article

Transits from the paper, bad paint drawings from me. The main dip comes from the planet, a shallower dip of variable time seems to be there, in agreement with expectations from a moon. We look at the system from below in the drawings.

The authors looked for signals of potential moons in the Kepler transit data. There is some weak evidence that a group of smaller moons exists, but the measurements are not accurate enough to pin that down on a star-by-star level. One particular planet, however, Kepler-1625b, has very curious features in all three observed transits. The Hubble telescope will observe the next transit in October this year.

If it is a moon, then the parent planet probably has 10 Jupiter masses while being a bit smaller than Jupiter, and the moon has Neptune size.

The star is probably quite old already and leaving the main sequence.

Wikipedia article

Transits from the paper, bad paint drawings from me. The main dip comes from the planet, a shallower dip of variable time seems to be there, in agreement with expectations from a moon. We look at the system from below in the drawings.

Last edited: