- #1

danjordan

- 15

- 0

[Mentor note: This thread was moved from General Physics due to it being homework related]

A friend and I were reviewing problems from a GRE subject which read:

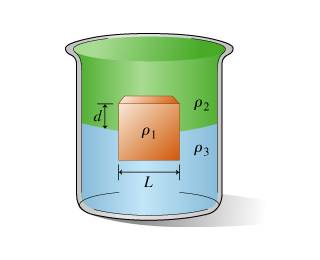

"A layer of oil with density 800 kg/m^3 floats on top of a volume of water with density 1000 kg/m^3. A block floats at the oil-water interface with 1/4 of its volume in oil and 3/4 of its volume in water, as shown in the figure above (below; i found a similar image). What is the density of the block?"

I solved it using the formula for the buoyant force, F = ρVg and the weight. So the balance was:

800gV/4 + 1000g*3V/4 = ρVg

950 kg/m^3 = ρ

In this I considered both buoyant forces, from oil and water to be directed upwards.

However, my friend considered the pressure at the depth of the top of the block to be P0, and at the bottom of the block to be P1. So (being 4h the height of the block, and A its top & bottom area):

P1 = P0 + ρ_oil*h*g + ρ_water*3h*g

When I work out the forces on the block (the weight of the oil above, the pressure on the bottom of the block) I'd get a balance:

P1*A = W + P0*A

Replacing the values we got the same value of density, 950 kg/m^3.

What is breaking my brain is the fact that I considered the buoyant force of the oil on the block to be upwards, while my friend considered it to be downwards on the block.

I want to know what is the real free-body diagram for the block and is the oil pushing down on the block or pulling it up?

A friend and I were reviewing problems from a GRE subject which read:

"A layer of oil with density 800 kg/m^3 floats on top of a volume of water with density 1000 kg/m^3. A block floats at the oil-water interface with 1/4 of its volume in oil and 3/4 of its volume in water, as shown in the figure above (below; i found a similar image). What is the density of the block?"

I solved it using the formula for the buoyant force, F = ρVg and the weight. So the balance was:

800gV/4 + 1000g*3V/4 = ρVg

950 kg/m^3 = ρ

In this I considered both buoyant forces, from oil and water to be directed upwards.

However, my friend considered the pressure at the depth of the top of the block to be P0, and at the bottom of the block to be P1. So (being 4h the height of the block, and A its top & bottom area):

P1 = P0 + ρ_oil*h*g + ρ_water*3h*g

When I work out the forces on the block (the weight of the oil above, the pressure on the bottom of the block) I'd get a balance:

P1*A = W + P0*A

Replacing the values we got the same value of density, 950 kg/m^3.

What is breaking my brain is the fact that I considered the buoyant force of the oil on the block to be upwards, while my friend considered it to be downwards on the block.

I want to know what is the real free-body diagram for the block and is the oil pushing down on the block or pulling it up?