Abdullah Almosalami

- 49

- 15

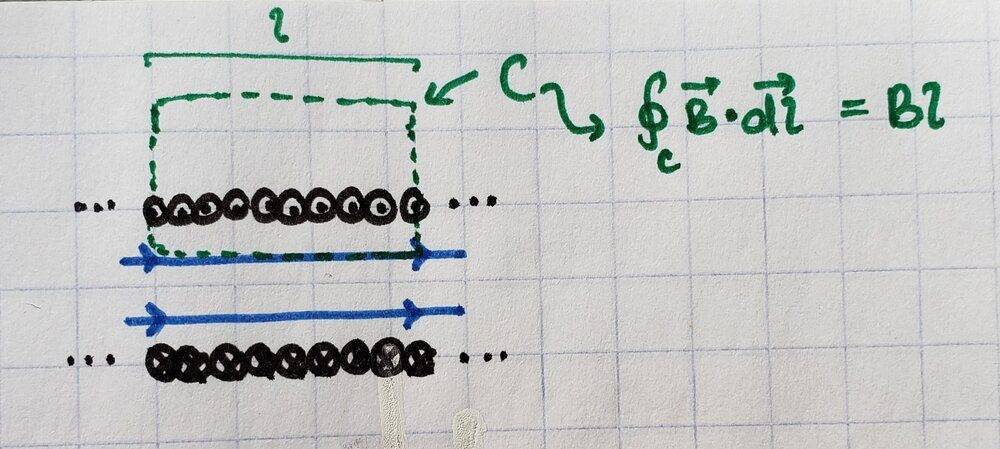

A classic example in textbooks is calculating the magnetic field inside a solenoid of length ##l## with ##N## turns and making the assumption that the magnetic field inside the solenoid is pretty uniform and outside it is 0. Using Ampere's law ## \oint_C \vec B \cdot d \vec l = \mu_0 I_{through} ## , if you do the line integral of ##\vec B \cdot d \vec l## over a well-chosen path with the assumptions in mind, you get ##B = \mu_0 \frac N l I##.

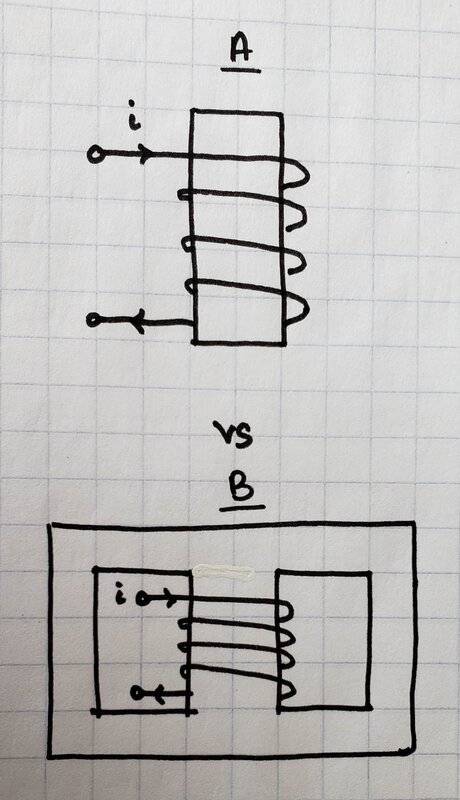

Now my question begins with placing a "core" material. Specifically,

Both are wound the same way, same current, # turns, and same core material. Also, say the cross-sectional area of the winding is the same in both cases. The first case 'A' is still a common example. If the core material has a magnetic relative permeability of ##\mu_r## (ignore the madness of hysteresis), then we just multiply that in with what was derived earlier, namely that now ##B = \mu_r \mu_0 \frac N l I##.

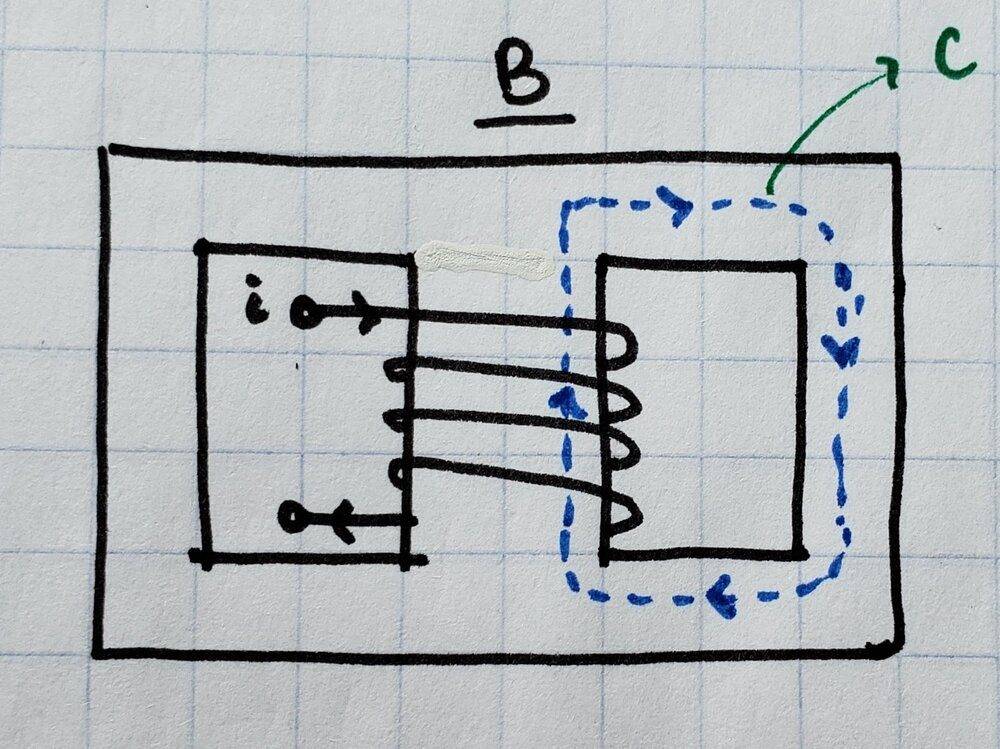

But in the second case 'B', I'm getting a little uneasy... I might naively do the same path of ##\vec B \cdot \vec dl## as shown in the first pic and use the same assumptions and conclude that the magnetic field is the same but I know that would be wrong. I might do a path like this:

and assume that the magnetic field is constant along the path, but that doesn't feel right either, and also would lead me to believe the magnetic field is less because ## \oint_C \vec B \cdot d \vec l## is larger with the same current and longer path so ##B## must be smaller. So I'm not sure how I'd tackle this...

Qualitatively, I know that B will have a stronger magnetic field inside the coil because I know that B has a higher inductance just from looking at inductors I have lying around in the school lab. If A and B have the same cross-sectional area, and you experimentally observe that ##L_A < L_B##, let's say by some factor ##\alpha##, then the magnetic field in the winding will also differ by the same factor since inductance is the amount of flux for a given current and they have the same cross-sectional area, and since the magnetic field in A is easier to calculate, I might use that to approximate what B's magnetic field would be.

I might hypothesize to explain why B has a stronger magnetic field by imagining each "section" of the frame that makes up B's core as contributing its own magnetic field to the inner part of the winding once it is magnetized, and then just superposition. B has more "frame" contributing magnetic field than A so yeah. Would that be the right idea?

Now my question begins with placing a "core" material. Specifically,

Both are wound the same way, same current, # turns, and same core material. Also, say the cross-sectional area of the winding is the same in both cases. The first case 'A' is still a common example. If the core material has a magnetic relative permeability of ##\mu_r## (ignore the madness of hysteresis), then we just multiply that in with what was derived earlier, namely that now ##B = \mu_r \mu_0 \frac N l I##.

But in the second case 'B', I'm getting a little uneasy... I might naively do the same path of ##\vec B \cdot \vec dl## as shown in the first pic and use the same assumptions and conclude that the magnetic field is the same but I know that would be wrong. I might do a path like this:

and assume that the magnetic field is constant along the path, but that doesn't feel right either, and also would lead me to believe the magnetic field is less because ## \oint_C \vec B \cdot d \vec l## is larger with the same current and longer path so ##B## must be smaller. So I'm not sure how I'd tackle this...

Qualitatively, I know that B will have a stronger magnetic field inside the coil because I know that B has a higher inductance just from looking at inductors I have lying around in the school lab. If A and B have the same cross-sectional area, and you experimentally observe that ##L_A < L_B##, let's say by some factor ##\alpha##, then the magnetic field in the winding will also differ by the same factor since inductance is the amount of flux for a given current and they have the same cross-sectional area, and since the magnetic field in A is easier to calculate, I might use that to approximate what B's magnetic field would be.

I might hypothesize to explain why B has a stronger magnetic field by imagining each "section" of the frame that makes up B's core as contributing its own magnetic field to the inner part of the winding once it is magnetized, and then just superposition. B has more "frame" contributing magnetic field than A so yeah. Would that be the right idea?