Leo Liu

- 353

- 156

- Homework Statement

- .

- Relevant Equations

- .

Question:

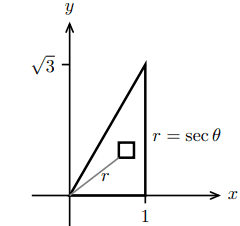

Diagram:

So the common approach to this problem is using polar coordinates.

The definition of infinitesimal rotational inertia at O is ##dI_O=r^2\sigma\, dA##. Therefore the r. inertia of the triangle is

$$I_O=\int_{0}^{\pi/3}\int_{0}^{\sec\theta}r^2r\,drd\theta$$

whose value is ##=\sqrt 3 /2##.

But when I used rectangular coordinates to solve this problem, I got a different answer. The steps are shown below.

$$\xcancel{\begin{aligned}

I_O&=\int_{0}^{1}\int_{0}^{2x}x^2+y^2\,dydx\\

&=\int_0^1x^2y+\frac{y^3} 3\Bigg|_0^{2x}dx\\

&=\int_0^12x^3+\frac 8 3x^3\,dx\\

&=\frac{x^4} 2+\frac 2 3x^4\Bigg|_0^1=\frac 7 6

\end{aligned}}$$

Can someone please tell me where my mistakes are? Thanks!

Edit:

$$\begin{aligned}

I_O&=\int_{0}^{1}\int_{0}^{\sqrt 3 x}x^2+y^2\,dydx\\

&=\int_0^1x^2y+\frac{y^3} 3\Bigg|_0^{\sqrt 3 x}dx\\

&=\int_0^1 \sqrt 3 x^3+\sqrt 3 x^3\,dx\\

&=\frac{2\sqrt 3}{4}=\frac{\sqrt 3}2

\end{aligned}$$

Diagram:

So the common approach to this problem is using polar coordinates.

The definition of infinitesimal rotational inertia at O is ##dI_O=r^2\sigma\, dA##. Therefore the r. inertia of the triangle is

$$I_O=\int_{0}^{\pi/3}\int_{0}^{\sec\theta}r^2r\,drd\theta$$

whose value is ##=\sqrt 3 /2##.

But when I used rectangular coordinates to solve this problem, I got a different answer. The steps are shown below.

$$\xcancel{\begin{aligned}

I_O&=\int_{0}^{1}\int_{0}^{2x}x^2+y^2\,dydx\\

&=\int_0^1x^2y+\frac{y^3} 3\Bigg|_0^{2x}dx\\

&=\int_0^12x^3+\frac 8 3x^3\,dx\\

&=\frac{x^4} 2+\frac 2 3x^4\Bigg|_0^1=\frac 7 6

\end{aligned}}$$

Can someone please tell me where my mistakes are? Thanks!

Edit:

$$\begin{aligned}

I_O&=\int_{0}^{1}\int_{0}^{\sqrt 3 x}x^2+y^2\,dydx\\

&=\int_0^1x^2y+\frac{y^3} 3\Bigg|_0^{\sqrt 3 x}dx\\

&=\int_0^1 \sqrt 3 x^3+\sqrt 3 x^3\,dx\\

&=\frac{2\sqrt 3}{4}=\frac{\sqrt 3}2

\end{aligned}$$

Last edited: