Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Paul E. Bland's book: Rings and Their Modules and am currently focused on Section 2.1 Direct Products and Direct Sums ... ...

I need help with some aspects of the proof of Proposition 2.1.4 ...

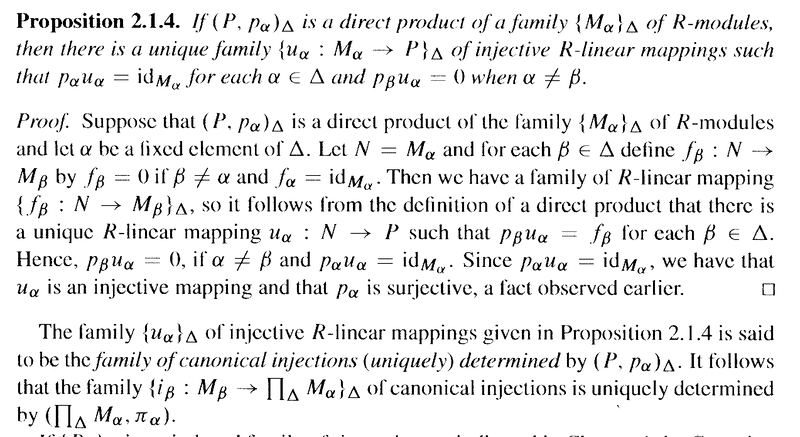

Proposition 2.1.4 and its proof read as follows:

In the above proof by Paul Bland we read the following:

In the above proof by Paul Bland we read the following:

" ... ... Since ##p_\alpha u_\alpha = \text{ id}_{ M_\alpha }##, we have that ##u_\alpha## is an injective mapping and that ##p_\alpha## is surjective ... ... "Can someone please explain exactly how/why ##u_\alpha## is an injective mapping ... ?Help will be appreciated ...

Peter

I need help with some aspects of the proof of Proposition 2.1.4 ...

Proposition 2.1.4 and its proof read as follows:

" ... ... Since ##p_\alpha u_\alpha = \text{ id}_{ M_\alpha }##, we have that ##u_\alpha## is an injective mapping and that ##p_\alpha## is surjective ... ... "Can someone please explain exactly how/why ##u_\alpha## is an injective mapping ... ?Help will be appreciated ...

Peter