Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading John M. Lee's book: Introduction to Smooth Manifolds ...

I am focused on Chapter 3: Tangent Vectors ...

I need some help in fully understanding Lee's conversation on directional derivatives and derivations ... ... (see Lee's conversation/discussion posted below ... ... )

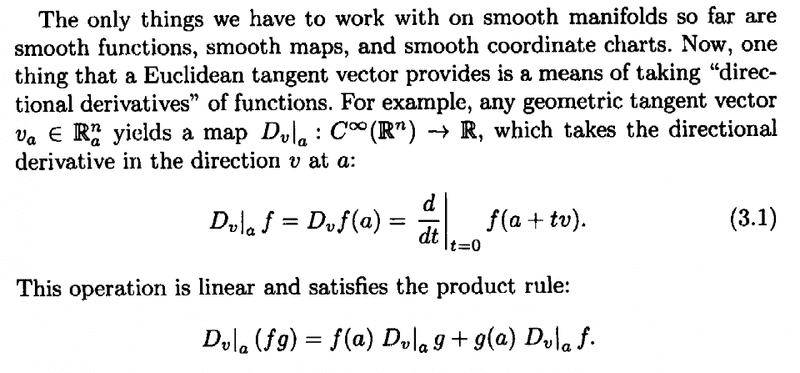

Lee defines a directional derivative and notes that taking a directional derivative of a function f in \mathbb{R}^n at a tangent vector v_a is a linear operation ... ... and follows a product rule ... ... that is, for two functions at v_a we have

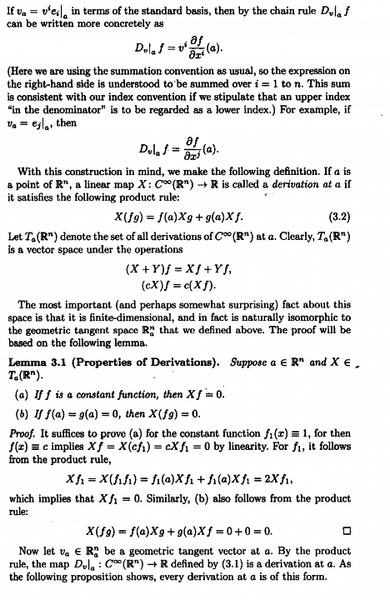

D_{v|_a} (fg) = f(a) D_{v|_a} g + g(a) D_{v|_a} fLee then defines a derivation ... that seems to generalise the directional derivative to any linear map that satisfies the product rule (see definition and (3.2) below ...

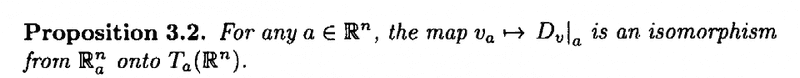

... ... BUT ... ... why does Lee need a 'derivation' ... why not stay with the the directional derivative ... especially as Proposition 3.2 (see below) establishes an isomorphism between \mathbb{R}^n_a by using a map:

v_a \mapsto D_{v|_a}

... that is a map that is onto the directional derivative ...Can someone please explain why Lee is introducing the derivation ... ? ... and not just staying with the directional derivative ... ?The relevant discussion in Lee, referred to above, is as follows:

I am focused on Chapter 3: Tangent Vectors ...

I need some help in fully understanding Lee's conversation on directional derivatives and derivations ... ... (see Lee's conversation/discussion posted below ... ... )

Lee defines a directional derivative and notes that taking a directional derivative of a function f in \mathbb{R}^n at a tangent vector v_a is a linear operation ... ... and follows a product rule ... ... that is, for two functions at v_a we have

D_{v|_a} (fg) = f(a) D_{v|_a} g + g(a) D_{v|_a} fLee then defines a derivation ... that seems to generalise the directional derivative to any linear map that satisfies the product rule (see definition and (3.2) below ...

... ... BUT ... ... why does Lee need a 'derivation' ... why not stay with the the directional derivative ... especially as Proposition 3.2 (see below) establishes an isomorphism between \mathbb{R}^n_a by using a map:

v_a \mapsto D_{v|_a}

... that is a map that is onto the directional derivative ...Can someone please explain why Lee is introducing the derivation ... ? ... and not just staying with the directional derivative ... ?The relevant discussion in Lee, referred to above, is as follows: