MarkFL

Gold Member

MHB

- 13,284

- 12

In analytic or coordinate geometry, we are often asked to work problems that involve using the perpendicular (shortest) distance between a point and a line in the plane. Here are two methods to find this distance:

Method 1:

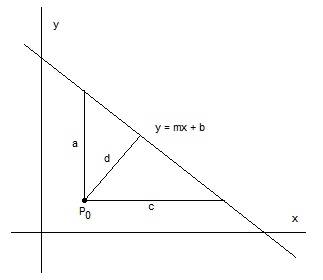

In the xy plane, we have a point $\displaystyle P_0\left(x_0,y_0 \right)$ separated from a line $\displaystyle y=mx+b$ by some distance $\displaystyle d>0$.

Extend a line segment from the point to the line such that the segment intersects perpendicularly with the line y. Label this segment d.

Now extend a vertical line segment from the point to the line and we find its length is $\displaystyle a=\left|mx_0+b-y_0 \right|$ (using $\displaystyle y\left(x_0 \right)-y_0$).

Next, extend a horizontal line segment from the point to the line and we find its length is $\displaystyle c=\left|x_0-\frac{y_0-b}{m} \right|$ (using $\displaystyle x_0-x\left(y_0 \right)$) thus:

$\displaystyle c=\left|\frac{mx_0+b-y_0}{m} \right|=\frac{a}{|m|}$

Please refer to the diagram:

By similarity, we have:

$\displaystyle \frac{d}{c}=\frac{\sqrt{a^2-d^2}}{a}$

$\displaystyle \frac{d}{\sqrt{a^2-d^2}}=\frac{c}{a}=\left|\frac{1}{m} \right|$

$\displaystyle \frac{d^2}{a^2-d^2}=\frac{1}{m^2}\:\therefore\:d^2=\frac{a^2}{m^2+1}\:\therefore\:d=\frac{a}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}$

Thus, we have:

$\displaystyle d=\frac{\left|mx_0+b-y_0 \right|}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}$

Method 2:

First, we find that the line perpendicular to $\displaystyle y=mx+b$ and passing through $\displaystyle P_0$ is:

$\displaystyle y=-\frac{1}{m}\left(x-x_0 \right)+y_0$

Solving the resulting linear system we find the common point to both lines is:

$\displaystyle \left(\frac{x_0+m\left(y_0-b \right)}{m^2+1},\frac{m\left(x_0+my_0 \right)+b}{m^2+1} \right)$

Now, using the distance formula for $\displaystyle P_0$ to the above point, we find:

$\displaystyle d=\sqrt{\left(x_0-\frac{x_0+m\left(y_0-b \right)}{m^2+1} \right)^2+\left(y_0-\frac{m\left(x_0+my_0 \right)+b}{m^2+1} \right)^2}$

The reader should verify that this reduces to:

$\displaystyle d=\frac{\left|mx_0+b-y_0 \right|}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}$

Comments and questions should be posted here:

http://mathhelpboards.com/commentary-threads-53/commentary-finding-distance-between-point-line-5966.html

Method 1:

In the xy plane, we have a point $\displaystyle P_0\left(x_0,y_0 \right)$ separated from a line $\displaystyle y=mx+b$ by some distance $\displaystyle d>0$.

Extend a line segment from the point to the line such that the segment intersects perpendicularly with the line y. Label this segment d.

Now extend a vertical line segment from the point to the line and we find its length is $\displaystyle a=\left|mx_0+b-y_0 \right|$ (using $\displaystyle y\left(x_0 \right)-y_0$).

Next, extend a horizontal line segment from the point to the line and we find its length is $\displaystyle c=\left|x_0-\frac{y_0-b}{m} \right|$ (using $\displaystyle x_0-x\left(y_0 \right)$) thus:

$\displaystyle c=\left|\frac{mx_0+b-y_0}{m} \right|=\frac{a}{|m|}$

Please refer to the diagram:

By similarity, we have:

$\displaystyle \frac{d}{c}=\frac{\sqrt{a^2-d^2}}{a}$

$\displaystyle \frac{d}{\sqrt{a^2-d^2}}=\frac{c}{a}=\left|\frac{1}{m} \right|$

$\displaystyle \frac{d^2}{a^2-d^2}=\frac{1}{m^2}\:\therefore\:d^2=\frac{a^2}{m^2+1}\:\therefore\:d=\frac{a}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}$

Thus, we have:

$\displaystyle d=\frac{\left|mx_0+b-y_0 \right|}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}$

Method 2:

First, we find that the line perpendicular to $\displaystyle y=mx+b$ and passing through $\displaystyle P_0$ is:

$\displaystyle y=-\frac{1}{m}\left(x-x_0 \right)+y_0$

Solving the resulting linear system we find the common point to both lines is:

$\displaystyle \left(\frac{x_0+m\left(y_0-b \right)}{m^2+1},\frac{m\left(x_0+my_0 \right)+b}{m^2+1} \right)$

Now, using the distance formula for $\displaystyle P_0$ to the above point, we find:

$\displaystyle d=\sqrt{\left(x_0-\frac{x_0+m\left(y_0-b \right)}{m^2+1} \right)^2+\left(y_0-\frac{m\left(x_0+my_0 \right)+b}{m^2+1} \right)^2}$

The reader should verify that this reduces to:

$\displaystyle d=\frac{\left|mx_0+b-y_0 \right|}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}$

Comments and questions should be posted here:

http://mathhelpboards.com/commentary-threads-53/commentary-finding-distance-between-point-line-5966.html

Last edited by a moderator: