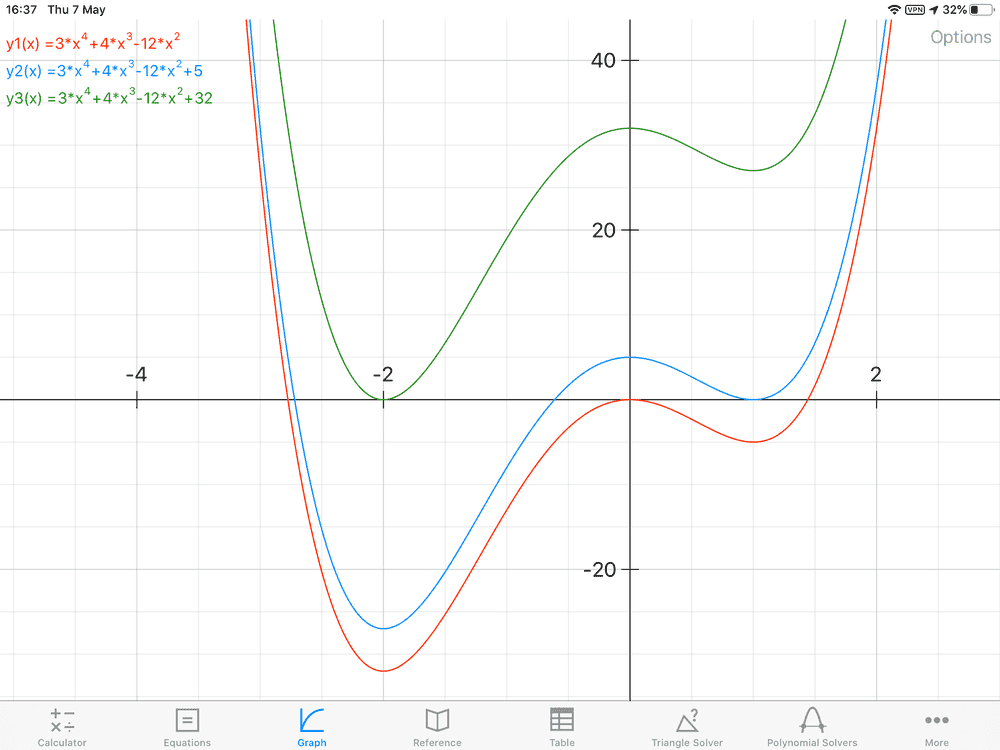

Surely it did not require very much to find out as well as 0 <

k < 5 giving four real roots,

k < 0 and 5 <

k < 32 give two real roots and

k > 32 gives zero real roots while if any of those inequalities are equalities, then there are two coincident roots. In no case are there four coincident roots.

chwala said:

i think i got it just a minute... the answer is ##0<k<5##. Is there not an algebraic way of finding these set of values?

etotheipi said:

I've no idea actually. There does exist a quartic discriminant but that is positive if all four roots are real or if all four roots are complex, so it doesn't really help.

Perhaps someone else knows an algebraic method... we'll have to wait and see!

This is a good question. One would like to know if any proof, argument, solution etc can be made on more minimal assumptions, or anyway if a certain different method can be used. Perhaps without using calculus and derivatives?

Maybe this sort of thing? The discriminant of the given polynomial is (with an irrelevant numerical factor removed)

$$ =k\left( k^{2}-37k+160\right) =k\left( k-5\right) \left( k-32\right)$$

That does give you the values as asked. It needs a bit more to know whether the ranges where it is negative give four or zero real roots, as mentioned by etothepi.

But against this it is a pain to calculate 5 x 5 determinant, even one with a number of zeros and units. I started, for the hell of it, but decided I shoudn't waste my time or encourage anyone else to waste theirs, so used WolframALpha to do it. Then it would be not too difficult to factorise – however we actually already knew the numerical values of its roots!

However you may be thinking, ah, but it is

purely algebraic whereas other methods talk about the derivative, i.e. involve calculus. Firstly let me say that one definition of the discriminant is the condition that a root of the polynomial equal a root of its derivative. at least, that is how you most easily get the formula (like the determinant above) for the discriminant so we haven't got away from derivatives. Still (now I think of it) you could argue from a different definition, that it is the product of all squares of differences between roots, which leads with more difficulty to the same formula. Anyway you will find all the algebra texts on the subject of the nature or localisation of roots, use derivatives very freely, and a great deal.But the clinching thing is that derivatives of polynomials don't have to be a calculus concept - they can be defined purely algebraically! So they are in my Bible (Old Testament) of algebraic equations*. I don't know whether this is common in other texts - you might easily miss it because you tend to rush cursorily over stuff one imagines one knows already - I know I did on first reading of Burnside & Panton. So it sounds like a good question, but I think at the end of the day there is nothing in it really. You best get the answers to this question just moving the curve up and down.

*The Theory of Equations, Burnside & Panton, 7th ed. 1912.

purely algebraic whereas other methods talk about the derivative, i.e. involve calculus. Firstly let me say that one definition of the discriminant is the condition that a root of the polynomial equal a root of its derivative. at least, that is how you most easily get the formula (like the determinant above) for the discriminant so we haven't got away from derivatives. Still (now I think of it) you could argue from a different definition, that it is the product of all squares of differences between roots, which leads with more difficulty to the same formula. Anyway you will find all the algebra texts on the subject of the nature or localisation of roots, use derivatives very freely, and a great deal.But the clinching thing is that derivatives of polynomials don't have to be a calculus concept - they can be defined purely algebraically! So they are in my Bible (Old Testament) of algebraic equations*. I don't know whether this is common in other texts - you might easily miss it because you tend to rush cursorily over stuff one imagines one knows already - I know I did on first reading of Burnside & Panton. So it sounds like a good question, but I think at the end of the day there is nothing in it really. You best get the answers to this question just moving the curve up and down.

purely algebraic whereas other methods talk about the derivative, i.e. involve calculus. Firstly let me say that one definition of the discriminant is the condition that a root of the polynomial equal a root of its derivative. at least, that is how you most easily get the formula (like the determinant above) for the discriminant so we haven't got away from derivatives. Still (now I think of it) you could argue from a different definition, that it is the product of all squares of differences between roots, which leads with more difficulty to the same formula. Anyway you will find all the algebra texts on the subject of the nature or localisation of roots, use derivatives very freely, and a great deal.But the clinching thing is that derivatives of polynomials don't have to be a calculus concept - they can be defined purely algebraically! So they are in my Bible (Old Testament) of algebraic equations*. I don't know whether this is common in other texts - you might easily miss it because you tend to rush cursorily over stuff one imagines one knows already - I know I did on first reading of Burnside & Panton. So it sounds like a good question, but I think at the end of the day there is nothing in it really. You best get the answers to this question just moving the curve up and down.