mk_gm1

- 10

- 0

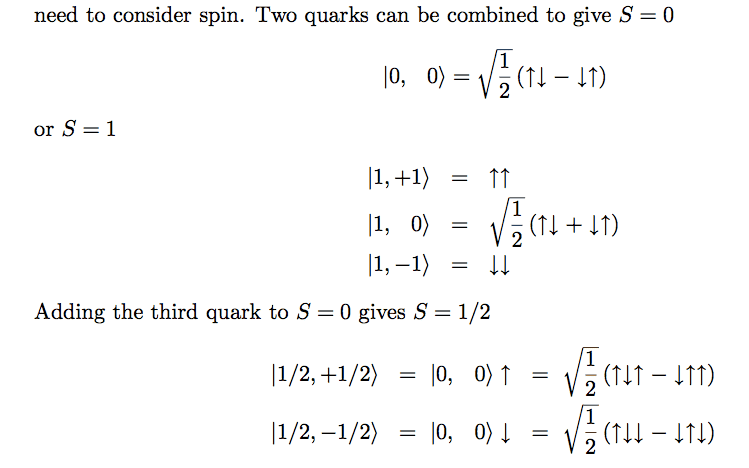

I was wondering if someone could help me to understand how you combine spin to form the total spin angular momentum number, S. Here's a selection from my notes:

Now as I understand it, S = (s_1 + s_2), (s_1 + s_2 - 1), ... |s_1 - s_2|. However, I don't really see how that leads to the conclusion that the singlet state above has S=0 and the triplet state has S=3.

And even if I can find a way to rationalise it for the 2 quark case, I don't have a clue what's going on when you add the third quark to S=0. I mean, I get that the spin of a quark is 1/2 so adding it to S=0 gives you S=3/2, but I don't see how S=1/2 corresponds to the states:

\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left(\uparrow \downarrow \uparrow - \downarrow \uparrow \uparrow \right) and \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left(\uparrow \downarrow \downarrow - \downarrow \uparrow \downarrow \right)

Could someone kindly explain this to me?

Now as I understand it, S = (s_1 + s_2), (s_1 + s_2 - 1), ... |s_1 - s_2|. However, I don't really see how that leads to the conclusion that the singlet state above has S=0 and the triplet state has S=3.

And even if I can find a way to rationalise it for the 2 quark case, I don't have a clue what's going on when you add the third quark to S=0. I mean, I get that the spin of a quark is 1/2 so adding it to S=0 gives you S=3/2, but I don't see how S=1/2 corresponds to the states:

\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left(\uparrow \downarrow \uparrow - \downarrow \uparrow \uparrow \right) and \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left(\uparrow \downarrow \downarrow - \downarrow \uparrow \downarrow \right)

Could someone kindly explain this to me?

Last edited: