SUMMARY

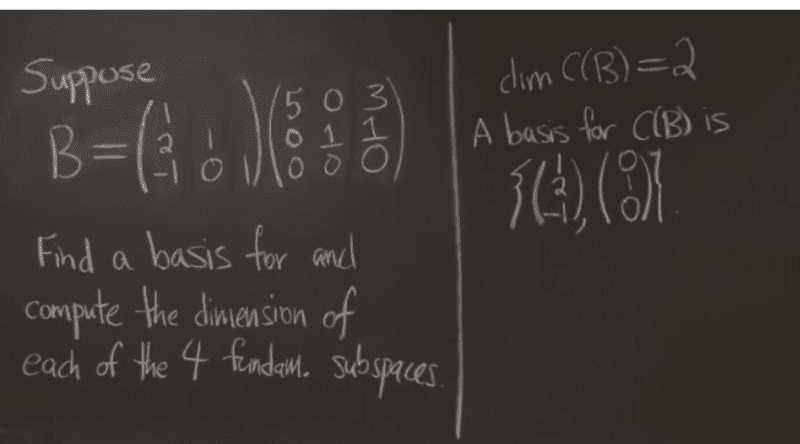

The discussion clarifies how the L matrix in the LU decomposition allows for the determination of the column space of matrix B. It establishes that the column space of B, denoted as C(B), is a subspace of the column space of L, C(L). Given that L is invertible and has linearly independent columns, the dimension of C(B) is 2, while C(L) is 3. The specific columns of L that contribute to C(B) are (1,2,-1)T and (0,1,0)T, which form a basis for C(B).

PREREQUISITES

- Understanding of LU decomposition

- Familiarity with concepts of column space and linear independence

- Knowledge of matrix rank and null space

- Basic linear algebra, including vector spaces

NEXT STEPS

- Study LU decomposition in-depth, focusing on its applications in solving linear systems

- Learn about the properties of column spaces and their relationship to linear transformations

- Explore the concepts of matrix rank and null space in various contexts

- Investigate the implications of linear independence in higher-dimensional vector spaces

USEFUL FOR

Students and professionals in mathematics, particularly those studying linear algebra, as well as data scientists and engineers working with matrix computations and transformations.