CGandC

- 326

- 34

Problem: Let ## (X,d) ## be a metric space, denote as ## B(c,r) = \{ x \in X : d(c,x) < r \} ## the open ball at radius ## r>0 ## around ## c \in X ##, denote as ## \bar{B}(c, r) = \{ x \in X : d(c,x) \leq r \} ## the closed ball and for all ## A \subset X ## we'll denote as ## cl(A) ## the closure of ## A ## ( sometimes denoted also as ## \bar{A} ## ).

Show that in ## \mathbb{R}^n ## with the standard metric it occurs that: ## cl(B(c, r))=\bar{B}(c, r) ##

Attempt:

## ( \subseteq ) ## Let ## \tau \in cl(B(c,r)) ##. There exists a sequence ## x_n \in B(c,r) ## s.t. ## x_n \rightarrow \tau ##

( From a theorem that says: ## x \in cl(B) \iff ## there exists a sequence ## x_n \in B ## , ## x_n \rightarrow x ## ).

Note that for all ## n \in \mathbb{N} ##, from the fact ## x_n \in B(c,r) ## we have ## d(c,x_n) < r ##. Also, since ## x_n \rightarrow \tau ## we have that ## d(x_n,\tau) \rightarrow 0 ##.

So by triangle inequality, we have for all ## n \in \mathbb{N} ## that ## d(c,x) \leq d(c,x_n) + d(x,x_n) ##, taking the limit we get ## d(c,x) \leq r ##.

## ( \supseteq ) ## Let ## \tau \in \bar{B}(c,r) ##, hence ## d(c,\tau) \leq r ##.

( Now we want to show that ## \tau \in cl(B(c,r)) ##, meaning for all ## r>0 ## we want to show ## B(\tau,r) \cap B(c,r) \neq \emptyset ## )

Let ## r>0 ##. Notice that ## \tau \in B(\tau,r) ## since ## d(\tau,\tau) =0 < r ##. In addition we have ## \tau \in \bar{B}(c,r) ## then ## d(\tau,c) \leq r ##.

If ## d(\tau,c)<r ## then ## \tau \in B(c,r) ##,

hence ## \tau \in B(\tau,r) \cap B(c,r) ##.

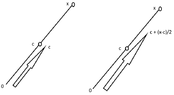

If ## d(\tau,c) = r ## then [ missing arguments for completing proof ].How to prove the "## ( \supseteq ) ##" side? I thought maybe I'd use the theorem "## x \in cl(B) \iff ## there exists a sequence ## x_n \in B ## , ## x_n \rightarrow x ## "; that means I'd show the existence of a sequence ## (x_k)_{k=1} \subseteq R^n ## s.t. ## (x_k)_{k=1} = ((x^{(1)}_i)_{i=1}^n,(x^{(2)}_i)_{i=1}^n,... ) ## s.t. ## x_k = (x^{(k)}_i)_{i=1}^n ## s.t. ## (x^{(k)}_i)_{i=1}^n \in R^n ## , but the question is how to define this sequence of sequences?

Show that in ## \mathbb{R}^n ## with the standard metric it occurs that: ## cl(B(c, r))=\bar{B}(c, r) ##

Attempt:

## ( \subseteq ) ## Let ## \tau \in cl(B(c,r)) ##. There exists a sequence ## x_n \in B(c,r) ## s.t. ## x_n \rightarrow \tau ##

( From a theorem that says: ## x \in cl(B) \iff ## there exists a sequence ## x_n \in B ## , ## x_n \rightarrow x ## ).

Note that for all ## n \in \mathbb{N} ##, from the fact ## x_n \in B(c,r) ## we have ## d(c,x_n) < r ##. Also, since ## x_n \rightarrow \tau ## we have that ## d(x_n,\tau) \rightarrow 0 ##.

So by triangle inequality, we have for all ## n \in \mathbb{N} ## that ## d(c,x) \leq d(c,x_n) + d(x,x_n) ##, taking the limit we get ## d(c,x) \leq r ##.

## ( \supseteq ) ## Let ## \tau \in \bar{B}(c,r) ##, hence ## d(c,\tau) \leq r ##.

( Now we want to show that ## \tau \in cl(B(c,r)) ##, meaning for all ## r>0 ## we want to show ## B(\tau,r) \cap B(c,r) \neq \emptyset ## )

Let ## r>0 ##. Notice that ## \tau \in B(\tau,r) ## since ## d(\tau,\tau) =0 < r ##. In addition we have ## \tau \in \bar{B}(c,r) ## then ## d(\tau,c) \leq r ##.

If ## d(\tau,c)<r ## then ## \tau \in B(c,r) ##,

hence ## \tau \in B(\tau,r) \cap B(c,r) ##.

If ## d(\tau,c) = r ## then [ missing arguments for completing proof ].How to prove the "## ( \supseteq ) ##" side? I thought maybe I'd use the theorem "## x \in cl(B) \iff ## there exists a sequence ## x_n \in B ## , ## x_n \rightarrow x ## "; that means I'd show the existence of a sequence ## (x_k)_{k=1} \subseteq R^n ## s.t. ## (x_k)_{k=1} = ((x^{(1)}_i)_{i=1}^n,(x^{(2)}_i)_{i=1}^n,... ) ## s.t. ## x_k = (x^{(k)}_i)_{i=1}^n ## s.t. ## (x^{(k)}_i)_{i=1}^n \in R^n ## , but the question is how to define this sequence of sequences?