Happiness

- 686

- 30

Is the chain rule below wrong?

What I propose is as follows:

Given that ##x_i=x_i(u_1, u_2, ..., u_m)##. If we define the function ##g## such that ##g(u_1, u_2, ..., u_m)=f(x_1, x_2, ..., x_n)##, then

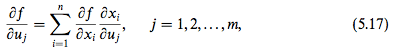

##\frac{\partial g}{\partial u_j}=\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\frac{\partial x_i}{\partial u_j}##.

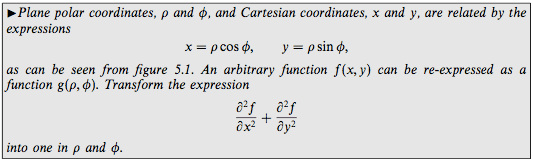

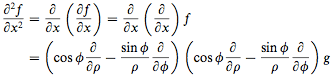

This version of chain rule is what is being used, it seems, in the example below when the answer given replaces ##f## with ##g## in the last line.

A related question is as follows:

Consider the function ##V(r)=\frac{1}{3}\pi r^2h##, where ##h## is a constant. Suppose ##r## is a function of ##t## such that ##r(t)=at^2##, where ##a## is a constant.

What do we call the function after substituting ##r## with ##at^2##, which gives ##\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2t^4h##?

I guess we have to give it a different name: ##W(t)=\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2t^4h##, because ##V(t)## would give ##V(t)=\frac{1}{3}\pi t^2h##. Then ##\frac{\partial V(t)}{\partial t}=\frac{\partial V(r)}{\partial r}##. Am I right?

If we still call it ##V## as follows: ##V(t) = \frac 1 3 \pi a^2 t^4 h##, we will run into a problem.

Since ##V(r)=\frac{1}{3}\pi r^2h##, when ##r=2##, we would write ##V(2)=\frac{1}{3}\pi\,2^2\,h##. But if we write ##V(t)=\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2t^4h##, when ##t=2##, we have ##V(2)=\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2\,2^4\,h##. Then ##V(2)\neq V(2)##.

What I propose is as follows:

Given that ##x_i=x_i(u_1, u_2, ..., u_m)##. If we define the function ##g## such that ##g(u_1, u_2, ..., u_m)=f(x_1, x_2, ..., x_n)##, then

##\frac{\partial g}{\partial u_j}=\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\frac{\partial x_i}{\partial u_j}##.

This version of chain rule is what is being used, it seems, in the example below when the answer given replaces ##f## with ##g## in the last line.

A related question is as follows:

Consider the function ##V(r)=\frac{1}{3}\pi r^2h##, where ##h## is a constant. Suppose ##r## is a function of ##t## such that ##r(t)=at^2##, where ##a## is a constant.

What do we call the function after substituting ##r## with ##at^2##, which gives ##\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2t^4h##?

I guess we have to give it a different name: ##W(t)=\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2t^4h##, because ##V(t)## would give ##V(t)=\frac{1}{3}\pi t^2h##. Then ##\frac{\partial V(t)}{\partial t}=\frac{\partial V(r)}{\partial r}##. Am I right?

If we still call it ##V## as follows: ##V(t) = \frac 1 3 \pi a^2 t^4 h##, we will run into a problem.

Since ##V(r)=\frac{1}{3}\pi r^2h##, when ##r=2##, we would write ##V(2)=\frac{1}{3}\pi\,2^2\,h##. But if we write ##V(t)=\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2t^4h##, when ##t=2##, we have ##V(2)=\frac{1}{3}\pi a^2\,2^4\,h##. Then ##V(2)\neq V(2)##.

Last edited: