SUMMARY

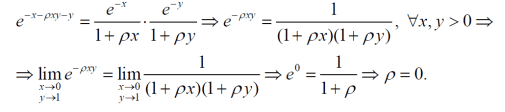

The discussion centers on the proof of the condition that ρ must equal zero for the identity exp(-ρxy) = 1/((1+ρx)(1+ρy)) to hold for all x, y > 0. Participants debate whether the proof is universal or limited to specific limits, emphasizing the importance of continuity and the implications of finding particular values of x and y. It is concluded that while ρ = 0 is a solution, the challenge lies in demonstrating that it is the only solution applicable across all x and y values.

PREREQUISITES

- Understanding of mathematical identities and proofs

- Familiarity with limits and continuity in calculus

- Knowledge of exponential functions and their properties

- Basic algebraic manipulation skills

NEXT STEPS

- Study the concept of mathematical identities and their proofs

- Learn about limits and continuity in calculus

- Explore the properties of exponential functions in depth

- Practice algebraic manipulation with complex equations

USEFUL FOR

Mathematicians, students studying calculus or algebra, and anyone interested in understanding the nuances of mathematical proofs and identities.