Kaldanis

- 106

- 0

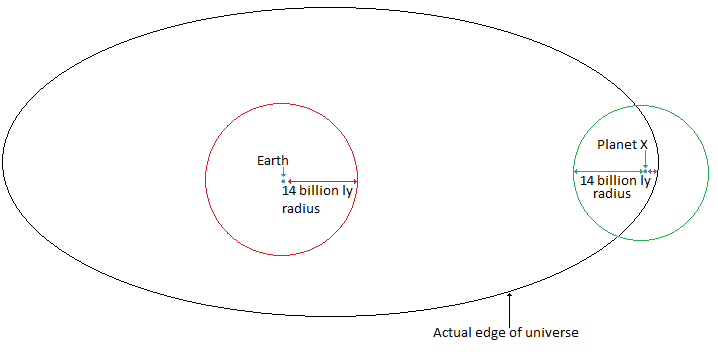

I think the picture explains it better than I can with words. Is it possible that we can only see a small sphere around our planet (red circle around Earth in the picture), but there could be a 'planet x' on the real edge of the universe that can see light from 14 billion light years away in one direction but perhaps only from 1 billion away in another direction? They could essentially see the edge of universe in one direction? (the purple arrow shows this edge they would see.)

Or, everything could be an infinite sphere and so we'd see the 14 billion light year radius no matter where we are in the universe. I'm guessing this is one of those things we will never know?

Or, everything could be an infinite sphere and so we'd see the 14 billion light year radius no matter where we are in the universe. I'm guessing this is one of those things we will never know?